These photos were compiled into an environmental education presentation intended to raise awareness of environmental problems in the countries and territories of Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia. It was prepared by Arthur Lyon Dahl, the Regional Ecological Adviser for the South Pacific Commission (now the Pacific Community) from 1974-1982 and organizer of the Secretariat for the Pacific Regional Environment Programme.

On an island, much of what you do on the land ends up in the sea, and if you have coral reefs that are very sensitive to pollution, they can be seriously damaged. Urban areas are major sources of pollution.

New Caledonia, polluted drainage in the city of Noumea, 1985

On an island almost everything drains into the sea or the lagoon, impacting mangroves, coral reefs and lagoon life.

Polluted water running to the lagoon, Noumea, 1985

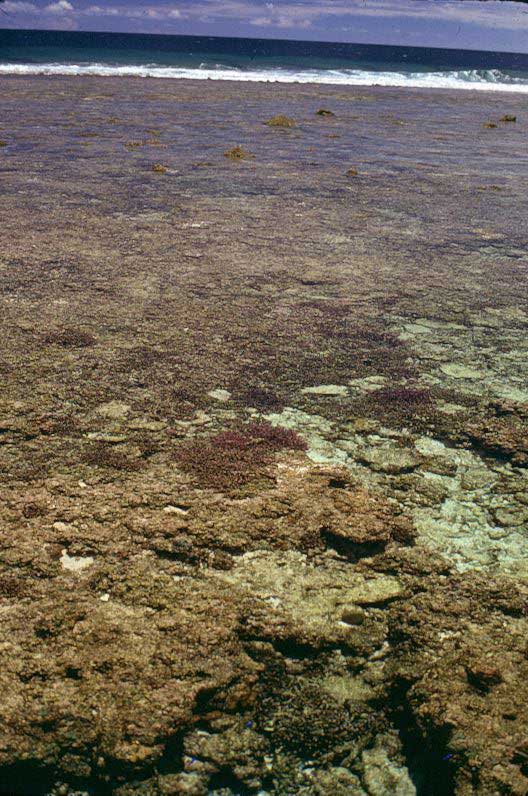

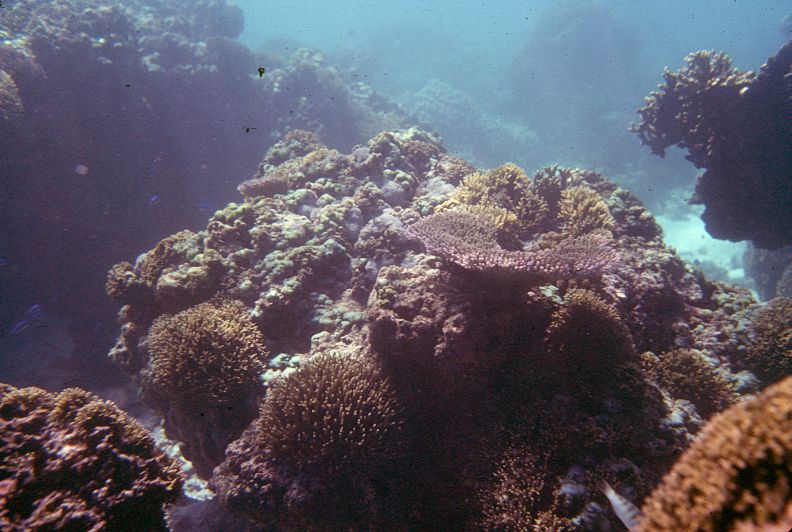

Coral reefs are one of the main environmental resources of tropical islands. Atolls are in fact entirely built by coral reef ecosystems. As Charles Darwin demonstrated, a new volcano emerging from the sea will be colonized by corals along its shallow sides where light is available. These will grow into a fringing reef. If the volcano gradually sinks or the sea level rises, the reef will keep growing to the surface, eventually forming a ring of coral around a lagoon with the volcanic island in the middle. Further sinking will leave only the ring of coral reef with a lagoon in the middle and islets of land were coral rubble has been piled on the reef during storms. Sometimes a rising seabed can life an atoll out of the water, making a raised coral island.

Coral reefs are highly productive ecosystems with thousands of species in great diversity. A healthy coral reef is full of fish.

Healthy coral reef around Tahaa, French Polynesia 1975

Coral reef lagoons are also very productive but sensitive to pollution.

Lagoon corals, seagrass and fish, Palau 1974

On a healthy reef, corals can grow to be very large.

Large healthy corals in the Solomon Islands 1975

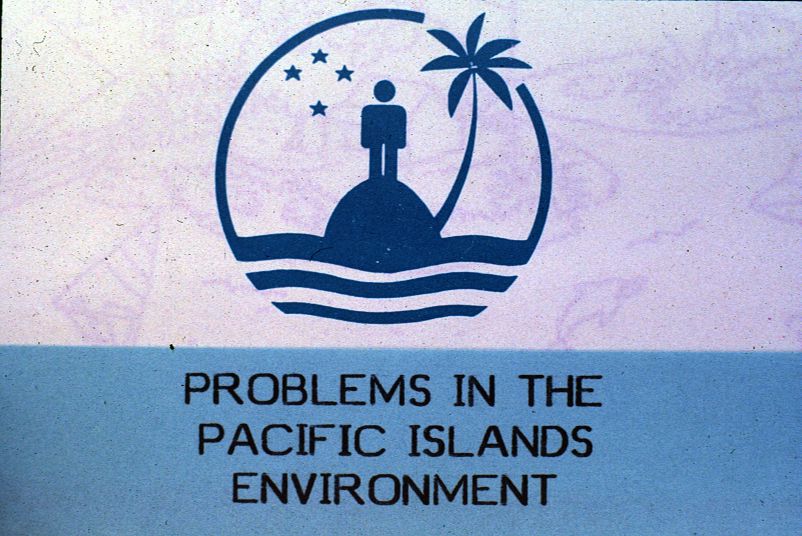

The shallow flats behind reefs are also productive areas.

Corals on the shallow flat behind the reef, Savaii, Samoa 1974

Many forms of reef life have important value to coastal communities for food and income. Some shells provide mother-of-pearl, as here in Micronesia.

Market for Trochus or Tectus, a reef snail with a thick mother-of pearl shell used for buttons, Pohnpei, Micronesia 1975

The corals, seaweeds and other reef life have calcium carbonate skeletons that become the beautiful white sand on tropical beaches. All that sand is generated by biological activity. Damage the reef, and the source of sand will be reduced.

Reef shallows with heavy sand production, Rarotonga, Cook Islands 1976

There are hundreds of coral species with many different shapes, forms and ecological functions that contribute to one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems on the planet. Reefs today are already seriously degraded and threatened by disappearance, unlike those shown in these pictures from nearly a half century ago.

Large reef corals, Guam 1974

The coral reefs of Upolu, Samoa, below, are shown in their former rich diversity. I later observed the first wave of Crown-of-Thorns starfish, Acanthaster, moving across the reef devouring all the corals and leaving dead white skeletons in their wake.

Coral reef, Upolu, Samoa 1976

Coral reefs are important for scientific research and for tourism, as well as for food and coastal protection, so their loss can have a major impact on island futures.

Reef tourism, diving on the coral reefs of Palau 1974

Coral reefs do best in clean pure seawater, and are very sensitive to pollution. Kaneohe Bay, on the island of Oahu in Hawai'i, saw many homes built along the shore, with their sewage and other pollution draining into the bay. It fertilized the massive growth of green bubble algae, smothering the corals as in the photo below.

Polluted reef overgrown by algae, Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii 1974

The Kanehoe Bay reefs looked like a nightmare from a horror film (below). Years later, when the sewage was collected and treated, the coral reef began to recover.

Polluted reef with corals overgrown by algae, Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, Hawaii 1974

When Pago Pago harbour in American Samoa was first studied by scientists in 1917-1920, it was lined with beautiful coral reefs, and the water was so clear that the corals on the bottom 20 meters (70 feet) deep could be identified from a boat. When I repeated the surveys in 1970 and later, many of the corals were dead and the water was very polluted by freshwater runoff, tuna cannery wastes and oil from ships (below).

Pollution by oil and cannery waste, Pago Pago harbour, American Samoa1975

The Crown-of-Thorns starfish, Acanthaster, is a rare natural predator of corals, but pollution can allow many more baby starfish to survive, and when they grow up they invade and destroy the corals on reefs. Seaweeds then take over, and it is hard for the corals to come back again.

Coral-eating Crown-of-Thorns starfish, Acanthaster, Palau 1974

When, during World War II, bombs dropped in the lagoon stunned many fish that were easy to catch, the local people learned an easy way to fish. Dynamite fishing became popular, but it destroys the coral reefs on which the fish depend for food and shelter.

Lagoon reef destroyed by dynamite fishing, Truk lagoon, Micronesia 1975

Since land is short on islands, there is strong pressure to dredge coral rubble from the lagoon and reef to make more land or create ports for boats. This both removes the corals and produces sediment that pollutes the water and can smother corals and other life far away.

Dredging on a coral reef for coastal construction, Tahiti, French Polynesia 1974

Many islands in the western Pacific have shallow areas with mangroves, that are very productive areas for fish.

Mangrove swamps, Palau 1974

Even many fish from the coral reefs come into the mangroves to reproduce, as the baby fish can more easily hide among the mangrove roots and find enough food to grow.

Reef fish breed among the roots of mangrove trees, Munda, Solomon Islands 1975

As island populations have grown and moved to the more urban centers, the environmental impacts of development have increases, in the islands as everywhere else.

The pressure for development in urban areas, as here in Apia, Samoa, means there is more dredging and filling. Here you can see how construction and dredging in the harbor in front of the Parliament Building has made the water murky and full of sediment.

Construction on the reef flat in front of Parliament Building, Apia, Samoa 1974

Although mangroves are very productive and important for fisheries, there is strong pressure to fill them in to make more land.

Filling in the mangroves, Upolu, Samoa 1974

Little by little, urban growth destroys the environment. Often tourist hotels are put in the most beautiful locations.

Th new Tusitala Hotel, Apia, Samoa 1974

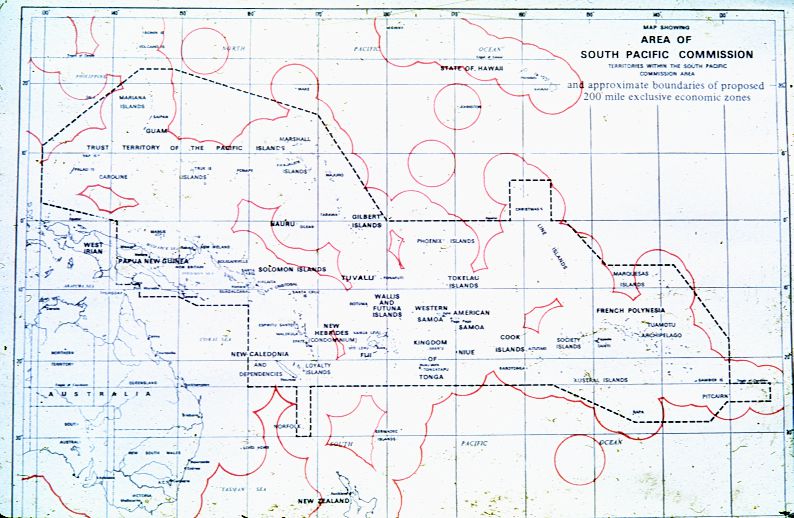

While the Small Island Developing States of the Pacific may seem like tiny dots in a giant ocean, by the time you add their Exclusive Economic Zones, they cover a major part of the tropical Pacific Ocean, making them large ocean States.

Exclusive Economic Zones in the Pacific Community (country names as they were in 1975)

Since the land area of islands is essentially limited, caring for the land and its biodiversity is important. Too often, forests have been logged to sell a little timber, or land cleared for agriculture, often on steep slopes where the heavy rains wash the soil into the sea. This development is very unsustainable.

Tropical forest, Tutuila, American Samoa 1975

Logging might seem like development, but once the trees are gone, what is left to support the life of local people?

Logging primary tropical forest on Niue 1974

Roads to open the forest for logging are very destructive, and important sources of soil erosion. In some areas of the Solomon Islands, the heavy machinery used for logging so compacted the soil that trees could no longer take root on one third of the land.

Logging roads in the Solomon Islands 1974

Sometimes the forestry practices of larger countries are tried in the islands, where the forest is cleared and replanted with a tree crop, but the soil is still damaged and may be compacted, the new trees take time to reach maturity and do not support the same biodiversity, and the small scale of the land available can make the effort uneconomic.

Tree nursery for reforestation on Savaii, Samoa 1974

In South-East Asia, vast areas of tropical rain forest have been destroyed to make way for palm oil plantations. An effort was made to try to do the same thing in the Solomon Islands.

Trial planting of oil palm, Solomon Islands 1975

Any disturbance in a tropical island forest can open the way for invasive species to replace the native flora. Hawai'i has been badly impacted in this way, and there were already many problems with invasive species in the Pacific Islands by the 1970s.

Invasive species at the forest edge, raspberries in Tahiti 1974

Saipan, in the Northern Marianas Islands, saw some of the worst fighting between the Japanese and the Americans during World War II. Its native vegetation was destroyed. I remember standing in one place and realizing that the soil beneath my feet was more fragments of iron, bullets and shell casings than earth. To heal the wounded land, a fast-growing nitrogen-fixing tree from the Americas, Leucaena, was planted as a first step to help the island recover.

Reforestation with Leucaena leucocephala, a fast-growing nitrogen-fixing tree, after war damage, Saipan, Northern Marianas 1985

Some larger islands saw significant colonial development, as with sugar cane in Fiji, where Indian workers were imported to harvest the sugar cane, and are now a majority of the population.

Sugar plantations in Fiji 1974

Where the center of an island is mountainous, and perhaps even an active volcano, development is often restricted to the more level coastal areas.

Mountainous terrain in the middle of Tahiti, French Polynesia 1975

Coastal development and mountains on Rarotonga, Cook Islands 1976

The Melanesian, Micronesian and Polynesian peoples who have inhabited the Pacific Islands for thousands of years had to learn to live sustainably in their island environments. The resulting traditional knowledge represented a rich store of environmental wisdom about the trees and plants, birds and sea life upon which they depended. In their indigenous world views, there was no separation between people and the natural world. Their ancestor might be a turtle or a shark, and legends and stories provided the framework of meaning for their lives, both spiritual and material. One family might be the master of the yams, while another had the skill with the fine knife to perform surgery or make sculpture. A village might have 30 different varieties of major crop plants, each adapted to a particular place or climatic condition, to ensure food security.

Island peoples had to develop their own specific kinds of agriculture adapted to their island environment. This might include shifting cultivation, as on the raised atoll of Niue, where a bit of forest is cleared to grow crops in the pockets of soil between the limestone rocks.

Shifting cultivation for food crops among limestone outcrops, Niue 1974

On the atolls, where the land is just a little coral rubble piled up on the reef by storms, and a lens of fresh water floats over the seawater in the middle of the island, growing taro requires digging down to the freshwater, making baskets with organic compost to provide a little soil, and planting a taro plant in the middle. The other main atoll food crops are breadfruit and coconuts.

Taro cultivation in baskets of organic matter at the water table, Butaritari atoll, Kiribati 1976

There was a traditional concept of protected areas for nature even in pre-colonial times. On Niue, about 20% of the central Huvalu forest was a taboo area with no entry allowed, maintaining a habitat for wildlife. It is still conserved as the Huvalu Forest Conservation Area.

Road near the Huvalu Forest Conservation Area, a reserve protected by traditional taboo over 20% of the island, Niue 1974

An important part of traditional knowledge concerned the management of the major food sources and environmental resources, limiting use to ensure sustainability. In the Lau Lagoon on Maleita in the Solomon Islands, where the traditional shell money was made, I was able to visit one of the traditional priests in his taboo house to learn how he managed the fishery, opening and closing parts of the lagoon to allow the shells to grow to maturity.

Taboo area with sacred huts of traditional priests who managed fisheries resources, Lau Lagoon, Maleita, Solomon Islands 1975

Different shell were used to provide black, white and orange disks to make the strings of traditional money.

Shells collected to make traditional shell money, Lau Lagoon, Maleita, Solomon Islands 1975

One of the fishermen showed me how he searched for the most desirable shells once the priest had given permission.

Fisherman collecting shells for shell money, Lau Lagoon, Maleita, Solomon Islands 1975

Where land is steep and rainfall is heavy, and land that is exposed is subject to rapid erosion. This not only degrades the soil, but it pollutes the water and can smother life in the lagoon and on the reef.

Soil erosion has become a major environmental problem in the high islands, when agriculture or construction remove the forest on the steep slopes.

Clearing for agriculture on steep hillsides, Tutuila, American Samoa 1974

In islands where there is a dry season, fire may be used to clear the land, or fire may accidentally escape into mountain areas.

Fire-cleared slopes at Wau, Papua New Guinea 1975

Any modern construction, whether of buildings or infrastructure, will have an impact on the land, and islands can be even more fragile in this respect.

Road construction, for example, is another major cause of soil erosion.

Road construction on steep ridges, Tahiti, French Polynesia 1974

Heavy rains can easily wash away major quantities of soil, down the streams and into the lagoon or on the fringing reef.

Roadside soil erosion, Tahiti, French Polynesia 1975

Erosion on steep slopes, Tutuila, American Samoa 1975

The raised ridge of coral rubble around an island, and the coastal forest on it, can also be an important protection from storm damage. Bulldozing this to make space for a house or hotel with a view can leave the buildings vulnerable to future storms.

Protective coastal forest cleared for construction, Rarotonga, Cook Islands 1976

Everyone must eat, so food production, especially on islands where there was no possibility to call for outside help in a disaster, required very sustainable and resilient agricultural practices.

On the raised coral islands that were once atolls, the layer of soil on top can be thin and easily destroyed, never to recover.

Narrow soil layer over limestone, raised atoll of Niue 1974

An attempt to copy modern agricultural techniques like mechanical plowing of large fields can be disastrous on a raised coral island like Niue, mixing the soil and underlying coral rock, lowering the soil pH and essentially sterilizing it so that hardly any plants can grow there.

Modern plowing destroying the fertile soil cover by mixing with underlying limestone, Niue 1974

On such degraded land, only a few pioneer plants like ferns and a few grasses can survive.

Degraded land where only some ferns and grasses can survive, Niue 1974

Despite tropical rainfall, water is often a scarce and valuable resource on islands, because the soil can be porous, rivers short or non-existent, and there are few lakes or other water bodies to store water for dry periods. On some islands rainwater caught on roofs is stored in water tanks. Water is essential for life.

Water is essential for life, New Caledonia 1985

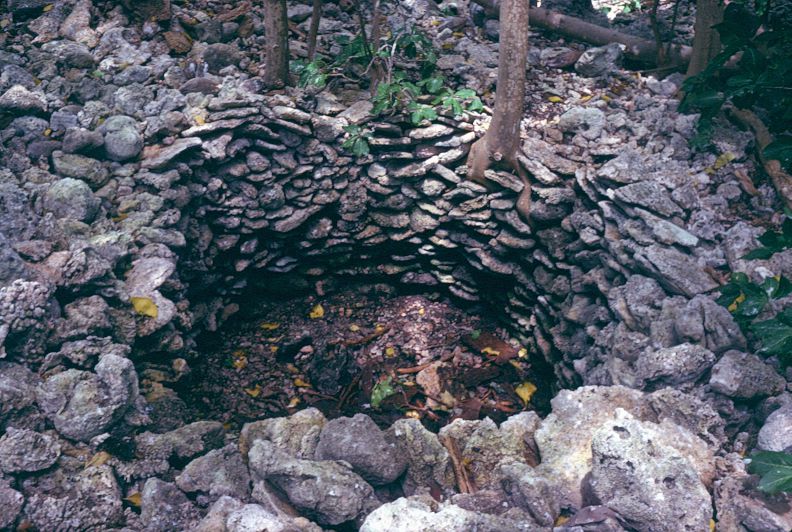

In the atolls, shallow wells in the center of the island can reach the freshwater lens, but if too much freshwater is drawn, it will become salty.

Traditional well down to the freshwater lens, Butaritari Atoll, Kiribati 1976

Recent volcanic islands made largely of lava flows and volcanic ash are too porous to retain much ground water. To collect water for a forestry nursery in Samoa, a plastic catchment was necessary.

Plastic rainwater catchment over porous volcanic surface to supply water for tree nursery, Savaii, Samoa 1974

Where there are streams, small dams can retain some water, but pollution needs to be avoided.

Water catchment for local water system, Palau 1974

In traditional island life, everything came from nature and could go back to nature. But when things imported from overseas become wastes, what do you do with them on a small island? Waste disposal is an enormous island problem.

Dump for abandoned vehicles, Niue 1974

To often, the easy solution is to dump the waste into a coastal landfill, perhaps in a mangrove swamp, but this pollutes and destroys the mangroves, and in a storm the waste can be washed out to sea, polluting the ocean as well.

Waste landfill in mangroves, Pohnpei, Micronesia 1975

Waste dump, Tongatapu, Tonga 1977

This was well before plastic pollution was recognized as a major global problem.

Wastes dumped in coastal mangroves, Upolu, Samoa 1974

Even the most beautiful areas can be despoiled by careless or negligent waste dumping.

Wastes dumped off ridge road, Tahiti, French Polynesia 1974

In the 1970s, there were few or no regulations about pesticides or other toxic chemicals in the islands and people were ignorant of the dangers. Below is what I found in a house I moved into in Noumea, New Caledonia. Imagine a bottle of dieldrin, a deadly pesticide now banned, with only a homemade label.

Typical household collection of pesticides, Noumea, New Caledonia 1985

Oil pollution was not yet a worry, and could be significant in ports or where there were many trucks or other machinery.

Oil pollution from fueling dock, Pago Pago harbour, Tutuila, American Samoa 1975

It was only with the wreck of the Torrey Canyon off the coast of England in 1967, and the Santa Barbara oil spill from a well off the California coast in 1969, that oil pollution finally made the world headlines. I was a student of marine biology in Santa Barbara at the time, and studied first-hand the damage that oil could do to coasts and marine life.

Tarred cliffs from the Santa Barbara Oil Spill, California 1969

The oil mixed with the beach sand and kept appearing for months.

Oil in the beach sand, Santa Barbara Oil Spill, California 1969

On the tourist beaches of Santa Barbara, the oil was soaked up with straw, and all the polluted sand and oil removed to be incinerated.

Santa Barbara Oil Spill, California 1969

By the 1970s, the islands were beginning to consider nature conservation and the creation of protected areas. New Caledonia declared a marine reserve in the lagoon near some small islands in the south, but there was no enforcement as I saw when I visited the reserve with the head of conservation and a distinguished French scientist and we found fishermen in the reserve.

Coastal Araucaria pines by the marine reserve, southern coast of NewCaledonia1976

In Palau, the Seventy Rock Islands included a unique marine lake in the middle of one island that was protected.

Rock Islands, Palau 1974

The marine lake had a limited ecosystem with one seaweed, one mussel, one fish and one jellyfish in large numbers.

Unique ecosystem of seaweed, mussel and jellyfish in marine lake, Rock Islands, Palau 1974

It was harder to see the need to protect the beauties of the traditional way of life.

Traditional seaside village, Savaii, Samoa 1974

Mining might seem like a good way to develop, and in colonial times it was used to extract wealth for the benefit of the colonial power, but once the valuable mineral is gone, only a degraded environment is left, and on an island with limited resources, that can be a permanent loss for those living there. The Pacific Islands have too many cases of the damage from mining. Ocean Island was abandoned when the phosphate ran out, and Nauru lost its main source of income when the same thing happened there, after many years of extreme wealth. Strip mining has ravaged much of New Caledonia, with one quarter of the world's nickel reserves. Giant mines in Papua New Guinea have a history of downstream pollution harming local people. Even quarrying for building material can have a significant impact on a small island.

Quarry for building material, Niue 1974

There was a gold rush in the 1930s in Papua New Guinea, leaving behind abandoned gold dredges and great piles of spoils.

Degraded land with abandoned gold dredge from 1930s, Bulolo, Papua New Guinea 1975

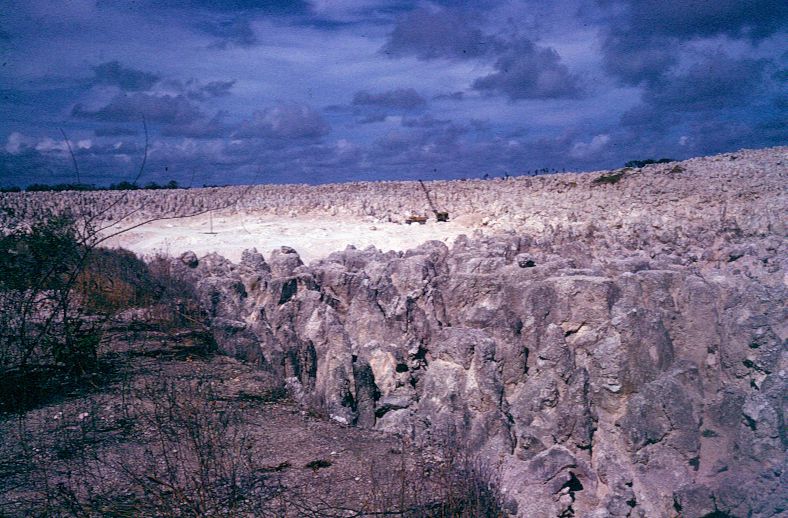

The raised atoll of the Republic of Nauru was covered in phosphate deposited by seabirds over many centuries. When I visited in 1976, still part of the island had not yet been mined, and I met one man who was earning from his former garden patch $100,000 every three months. The phosphate ran out at the end of the 20th century, and the country has fallen on hard times.

Phosphate mining on raised atoll of Nauru 1976

Phosphate had to be dug out from between the limestone pinnacles.

Phosphate mining on Nauru 1976

After mining, the land was barren and useless for any other purpose, and freshwater was brought in by the ships that carried away the phosphate.

Rocky surface left after phosphate mining on Nauru 1976

In Papua New Guinea, the Bougainville Mine at Panguna producing copper, gold and silver was one of the largest of its time. When I visited it in 1978 with a regional training course on environmental planning and management, we were shown how environmentally responsible the company claimed to be, but in fact it was just the reverse, leading eventually to revolution on Bougainville Island and the closure of the mine.

Copper mine at Panguna, Bougainville Island, Papua New Guinea 1978

The tiny-looking trucks down in the mine could each carry 160 tonnes of ore.

Copper mine at Panguna, Bougainville Island, Papua New Guinea 1978

The water pollution draining from the mine impacted everyone down the Jaba River.

Sediment and pollution runoff from copper mine at Panguna, Bougainville Island, PNG 1978

My environmental trainees measured the levels of pollution downstream from the mine. The river water was more like liquid clay.

Measuring the pollution in the Jaba River from copper mine at Panguna, Bougainville Island, PNG 1978

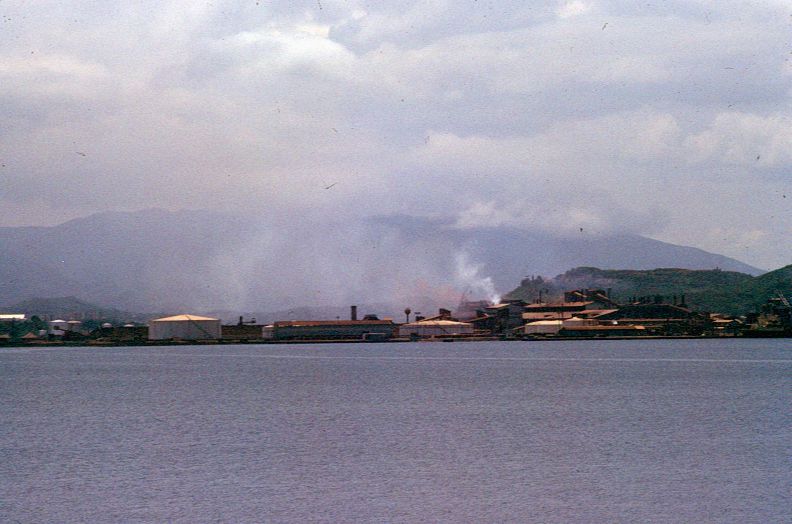

The island of New Caledonia, an ancient continental fragment with unusual rocks high in minerals, has been subjected to extreme strip-mining high in the mountains, causing enormous erosion and pollution. Much of the unique southern forest was burned in the 19th century to make prospecting for minerals easier. The nickel refinery in the city of Noumea (below) provided one eighth of the world's nickel refining capacity when I lived there. Tourist brochures even invited visitors to come and admire the beautiful multi-coloured smoke of the refinery as a tourist attraction. How times have changed! No one mentioned the high levels of cancer that one of my medical colleagues identified in those living near the refinery.

Nickel smelter, Noumea, New Caledonia 1985

This is the end of this pictorial exploration of environmental problems in the Pacific Islands as we understood and experienced them in the 1970s and after. One result of my work was the creation of SPREP, the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (https://www.sprep.org/), now an intergovernmental organization of all the Pacific Island countries and territories working to find solutions to all the environmental problems demonstrated here.