MARK TOBEY |

American artist 1890-1976

Page by Arthur Lyon Dahl

The major contribution of Mark Tobey to twentieth century art is still inadequately appreciated, perhaps because he never tried to market himself or his art as did many of his contemporaries. He drew inspiration and technique from many cultures of East and West, from cities, nature and science, and created art that broke new ground and influenced many other artists. In particular, his efforts to reflect spirituality in art set him apart from his secular century, but will ensure that he is remembered long after most of his contemporaries. He accepted the Bahá'í Faith in 1918 and, for the rest of his life, Bahá'í principles and concepts interacted with his sensitive soul and creative imagination as he sought new ways to express what he felt and experienced. The art that he has left to humanity reflects that life-long journey. It resonates with our spirits and enriches our lives.

My interest in Mark Tobey's work is lifelong, because I grew up in a house full of his paintings, and have lived with them ever since. My parents, Joyce and Arthur Dahl, were also Bahá'ís and close friends of Mark, and their collection grew over the years to 100 works. I photographed all of them so that I could give lectures on Mark and his art. I myself met Mark on several occasions, the last time in Basel a few years before his passing. I was a student in France at the time of his great retrospective in the Louvre in Paris in 1961, and spent several weekends admiring the 286 paintings gathered there. Since then I have tried to visit as many of his expositions as I could, and have personally seen and studied over 500 of his works.

Mark Tobey in his studio 1949 (photo by Larry Novak)

The

best web site for information on Mark Tobey is maintained by the Committee Mark Tobey at http://www.cmt-marktobey.net. It includes a full chronology of his life, a comprehensive listing of expositions of his work, and an extensive bibliography. Therefore my page here only tries to provide a brief introduction to Mark Tobey, in the hope that others will be attracted to his art and pursue their interest further. While there are many published catalogues of Tobey exhibits and some books on him, most are difficult to obtain today. One recommended work is Mark Tobey: Art and Belief, by Arthur L. Dahl and others, published by George Ronald, Oxford, 1984. In includes my article The

Fragrance of Spirituality, originally published in The

Bahá'í World, Vol. XVI, 1978.

The

best web site for information on Mark Tobey is maintained by the Committee Mark Tobey at http://www.cmt-marktobey.net. It includes a full chronology of his life, a comprehensive listing of expositions of his work, and an extensive bibliography. Therefore my page here only tries to provide a brief introduction to Mark Tobey, in the hope that others will be attracted to his art and pursue their interest further. While there are many published catalogues of Tobey exhibits and some books on him, most are difficult to obtain today. One recommended work is Mark Tobey: Art and Belief, by Arthur L. Dahl and others, published by George Ronald, Oxford, 1984. In includes my article The

Fragrance of Spirituality, originally published in The

Bahá'í World, Vol. XVI, 1978.

Mark Tobey was born in 1890 and raised in the American midwest, living a life like Tom Sawyer along the riverside. He had little art training, but started as a draftsman and soon became a fashionable portrait painter in New York. In 1918 he learned of the Bahá'í Faith through another artist, Juliet Thompson, and soon became a Bahá'í. He moved to Seattle, Washington, and began to experiment with new directions and forms of exploration in his art, gradually breaking free of Western artistic conventions and bridging Oriental and European art, and in the process finding ways to express multiple space. The best way to understand his accomplishments and to learn his artistic language is through his own words:

"One night [ca. 1920] I was in my studio drawing my own portrait. On the ceiling, a light. All of a sudden I thought: suppose I were a fly. I could fly on to the easel, fly around me, go for a walk on my back, go up to the wall, etc.... In this closed space I projected the path taken by the fly: no more frame, no more Renaissance." (Whitechapel catalog, 1962, p.9)

In the 1930s he moved to England to Dartington Hall, where he met the potter Bernard Leach and taught him the Bahá'í Faith. Together they travelled to the orient, where Tobey spent time in a Zen monastery and studied calligraphy.

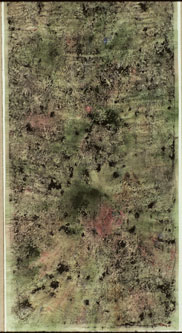

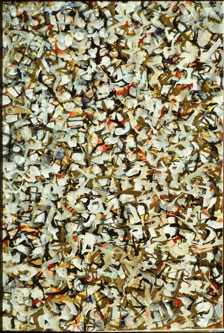

Chinese Grocery 1957

"In a broad comparison between Eastern and Western Art it could be said that in the East artists have been more concerned with line and in the West with mass. Certainly the Eastern artists were far from the Renaissance concept as expressed by my Chinese friend who observed, 'The Western artists' paintings are framed holes.' Of course today the illusionistic style is dead and has been for some time. One hears it said often that Picasso marks the end of the classic period in the West. Where then shall we turn?

"A few decades ago we went to the galleries to see herons in the marshes, winter scenes at twilight, apples on a table. Nowadays we go to see lines, squares and great squashes of paint. Much that passes as abstract art whether in Asia or the U.S. and Europe is not necessarily related to Simplicity, Directness, and Profundity. Perhaps if we omit the last word, the other two tally. That abstract art has in many ways become an Academy appears certain. But somewhere in this and in what we saw before, there were a few paintings that radiated the spirit and it is these we seek, no matter what garment is worn. When I resided at the Zen monastery I was given a sumi-ink painting of a large free brush circle to meditate upon. What was it? Day after day I would look at it. Was it selflessness? Was it the universe - where I could lose my identity? Perhaps I didn't see its aesthetic and missed the fine points of the brush which to a trained oriental eye would reveal much about the character of the man who painted it. But after my visit I found I had new eyes and that which seemed of little importance became magnified in words, and considerations not based on my former vision. When I saw a great dragon painted in free brush style on a ceiling in a temple in Kyoto I thought of the same rhythmical power of Michelangelo - the rendering of the form was different - the swirling clouds accompanying his majestic flight in the heavenly sphere were different but the same power of the spirit pervaded both.

"'Let nature take over in your work.' These words from my old friend Takizaki were at first confusing but cleared to the idea - 'Get out of the way.' We hear some artists speak today of the act of painting. This in its best sense could include the meaning of my old friend. But a State of Mind is the first preparation and from there this action proceeds. Peace of Mind is another ideal, perhaps the ideal state to be sought for in the painting and certainly preparatory to the act.

"This is not easy to accomplish, but in a highly industrialized and competitive society it could be a fine antidote. Not to look for fine draughtsmanship nor fine color - perhaps no color - but directness of spirit will become for us a new point of view as the arts of the East and of the West draw closer together." (from Japanese Traditions and American Art, quoted in Whitechapel catalog, p. 18-19, Louvre 5-6)

"The old Chinese used to say: 'It is better to feel a painting than to look at it.' So much today is only to look at. It is one thing to paint a picture and another to experience it: in attempting to find on what level one accepts this experience, one discovers what one sees and on what level the discovery takes place. Christopher Columbus left in search of one world and discovered another." (letter to Marion Willard, Whitechapel catalog, p. 15, Louvre 2)

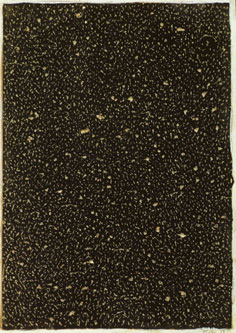

Fire Dancers 1957

"I presume (current painting) must be looked at for what the Orientals would admire - the original energies. This is so much admired in calligraphy." (letter to Arthur L. Dahl, 20 August 1957, Dahl catalog p. 12)

"In China and Japan I was freed from form by the influence of the calligraphic. I already knew this means of expression when I was living in Seattle. I studied this calligraphic method with Chinese painter Ten Kuei. I did not go to China or Japan to find something for my works, I went there because I had the opportunity to do so.

"The development of my work has been I feel more subconscious than conscious. I do not work by intellectual deductions. My work is a kind of self-contained contemplation." (quoted in Stedelijk catalog, 1966)

Tobey experimented with many styles and media, inventing what has been called white writing as a way of expressing light, such as the city lights in his famous "Broadway Boogie" of 1938.

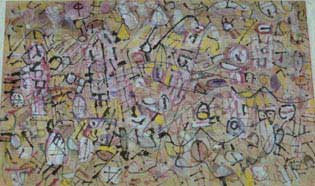

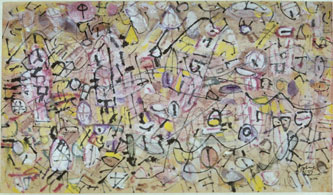

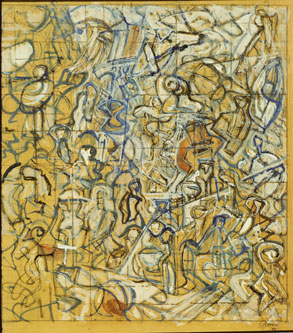

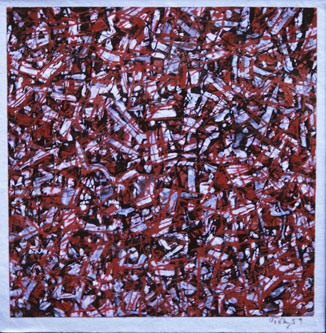

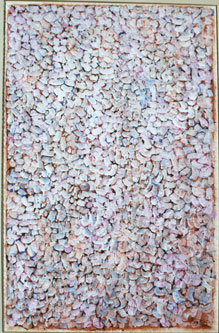

Carnival 1954

"For a long time I had tried to associate the town and town life with my work. I had eventually felt that I had found a technical equivalence which enabled me to capture what specially interested me. The lights, the electric cables of the trolleys, the human streams directed by, through and round prescribed limits, on the whole not so different from those of chlorophyll in the veins of a leaf. Of course I was not always conscious of what I was doing and my method often ended in results contrary to those I hoped for, because there were no rules around me to use as a basis for comparison. Just as the first cubists, I did not dare use color, for the problems were already complicated enough without adding that one. Color would, of course, come back later." (quoted

in Whitechapel catalog, 1962, p. 11-12)

"White lines in movement symbolize light as a unifying idea which flows through the compartmented units of life bringing a dynamic to men's minds, ever expanding their energies toward a larger relativity." (quoted in Palace of Legion of Honor catalog, 1951)

"I am accused often of too much experimentation, but what else should I do when all other factors of man are in the same condition? Shall any member of the body live independently of the rest? I thrust forward into space as science and the rest do. My activity is the same, therefore my end will be similar. The gods of the past are as dead today as they were when Christianity overcame the Pagan world. The time is similar, only the arena is the whole world.

"New seeds are no doubt being sown which mean new civilizations and, let us hope, cultures too. If I do anything important in painting some age will bring it forth and understand. One naturally looks forward to the time when absolutes will reign no more and all art will be seen as valid, with many thanks to Picasso and the brave men of European painting and to those who have fostered such ideas in this country. Shall we, as we view the increasingly darkening sky, not hope for a Byzantium, some spot to keep alight the cultural values? For what else shall we live?" (statement by the artist, Portland/SF/Detroit catalog, 1945-46)

To make a living he taught art, and for most of his life he received little recognition, with small shows on the West Coast and in New York. While living in Seattle, he spent much time in New York and associated with the artists who became the abstract expressionists of the New York School. His own work had a significant catalytic influence on painters such as Jackson Pollack. Yet his work remained highly varied as he experimented constantly to the end of his life, and he never developed a consistent style.

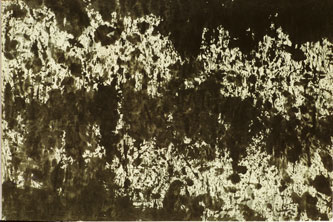

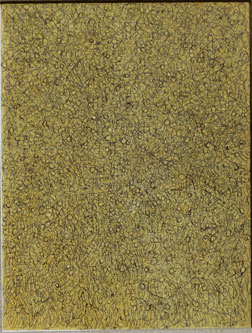

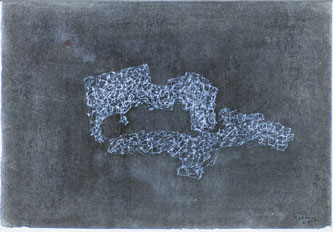

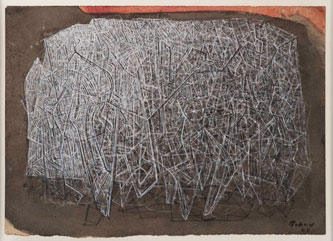

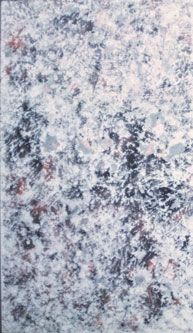

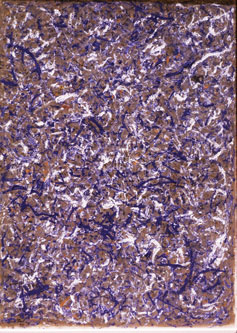

Forest Fire 1956

"Over the past 15 years, my approach to painting has varied, sometimes being dependent on brush-work, sometimes on lines, dynamic white strokes in geometric space. I have never tried to pursue a particular style in my work. For me, the road has been a zig-zag into and out of old civilizations, seeking new horizons through meditation and contemplation. My sources of inspiration have gone from those of my native Middle West to those of microscopic worlds. I have discovered many a universe on paving stones and tree barks. I know very little about what is generally called 'abstract' painting. Pure abstraction would mean a type of painting completely unrelated to life, which is unacceptable to me. I have sought to make my painting 'whole' but to attain this I have used a whirling mass. I take up no definite position. Maybe this explains someone's remark while looking at one of my paintings: 'Where is the center?'." (letter dated 1/2/55, Whitechapel catalog, p. 13)

Tobey's first real international recognition came when he won the Grand Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale in 1958. He was then 68 years old. In 1961 he was honored with a major retrospective in the Louvre in Paris, followed by another in the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1962. He was then considered in Europe to be the greatest living American painter, yet he was still almost unknown in his own country, which was not attuned to the spiritual dimension of his work.

"As to the content of my work, well in spite of the comments regarding my interest in Zen, it has never been as deep as my interest in the Bahá'í Faith. The need of a unifying idea is so clearly stated in the writings of its founder, Bahá'u'lláh, and so necessary as an explanation of our age with its new horizons for all men and its relative dangers from men of our age, it would seem to me to be the living core of what I could term Modernism." (conversation with Arthur L. Dahl, 1962)

"One is so surrounded by the scientific naturally one reflects it, but one needs (I mean the artist now) the religious side. One might say the scientific aspect interests the mind, the religious side frees the heart. All are interesting." (letter to Arthur and Joyce Dahl, 26 April 1957, Dahl catalog, p. 15)

"The earth has been round for some time now, but not in man's relation to man nor in the understanding of the arts of each as part of that roundness. As usual we have occupied ourselves too much with the outer, the objective, at the expense of the inner world wherein the true roundness lies." (from MMA catalog 1946, quoted in Seitz 1962, p. 9)

"...The cult of space can be as dull as that of the object. The dimension that counts for the creative person is the space he creates within himself. This inner space is closer to the infinite than the other, and it is the privilege of a balanced mind - and the search for an equilibrium is essential - to be as aware of inner space as he is of outer space. If he ventures in one, and neglects the other, man falls off his horse and the equilibrium is broken." (quoted in Louvre catalog, 2nd page, Collette Roberts, p. 43)

"Of course we talk about international styles today, but I think later on we'll talk about universal styles... the future of the world must be this realization of its oneness, which is the basic teaching as I understand it in the Bahá'í Faith, and from that oneness will naturally develop a new spirit in art, because that's what it is. It's a spirit and it's not new words and it's not new ideas only. It's a different spirit. And that spirit of oneness will be reflected through painting." (conversation with Arthur L. Dahl, 1962, Dahl catalog, p. 15)

Tobey moved to Basel, Switzerland in the early 1960s to escape the effects of his success, which had made it too hard to concentrate on his painting. He continued painting until he was over 80, still experimenting with new media. He died in Basel in 1976.

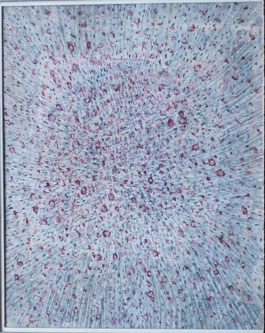

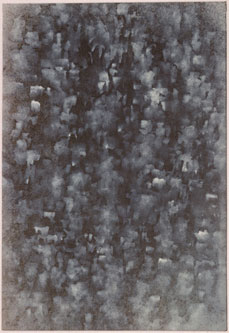

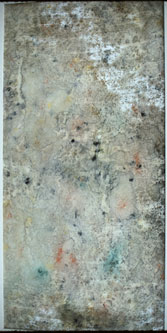

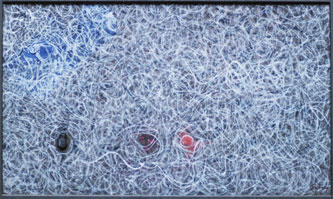

Aerial Centers 1967

Of course, the above quotations can only give a little idea of Tobey's artistic "language" and what he was trying to express. The next step is to see and experience his paintings, and this also takes some time. As Lionel Feininger said of Tobey: his paintings contain the element of time, they unfold their contents gradually.

Unfortunately the web is not such a good medium to show his paintings with their fine brushwork and subtle colors; the files become impossibly large, and any small selection, or even the full Dahl collection (below) does not do justice to the variety of his work. There are occasional exhibitions of his paintings, at least in Europe. They are often announced on the Committee Mark Tobey web site: http://www.cmt-marktobey.net

One interesting connection between artists is the inspiration that Mark Tobey's painting "Lovers of Light" provided to the Canadian architect Siamak Hariri in the conception of the Baha'i House of Worship in Chile, which I discovered in 2008 (see separate page).Click on the paintings to see a larger version

These are my own photographs of the original paintings, so the quality is not very good.

Copyright (c) by Arthur Lyon Dahl, all rights reserved

Tobey Remembered Interview with Arthur and Virginia Barnett (1990) regarding their friendship with Mark Tobey. Includes music composed by Tobey. From a videotape in the collection of Arthur and Joyce Dahl.

MARK TOBEY |

From the time that Joyce and Arthur L. Dahl first met Mark Tobey in the mid-1940s, they fell in love with his works and began collecting them, starting with The New Day (1945) and continuing to the end of his life. After Mark Tobey moved to Basel, Switzerland, the Dahls helped him to clear out his Seattle studio, acquiring both some very early works and more recent ones, along with some other art works and possessions that belonged to Tobey. In the end their collection amounted to about 100 works (not counting 28 Dartington drawings), to which their son Arthur Lyon Dahl made a few additions of his own. Many of these works have now been dispersed, some given to the Stanford Art Gallery and the Archives of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States, others sold, and some still remaining in the Dahl family.

This page documents the full Dahl collection as photographed by Arthur Lyon Dahl in 1966 and 1968-70 with one exception. A painting first purchased as untitled and later named Foundations of Harmony by Mark Tobey on a visit to the Dahls, was on loan the first time the collection was photographed, and had been stolen while the paintings were at Gumps in San Francisco for reframing two years later, so no photographic record remains.

Click on the paintings to see a larger version

.

.  .

.

Martha Graham 1928; untitled 1929; untitled ca. 1930

See also the Dartington Hall prints of pen drawings on wet paper 1931-1932, and the undated painting on a spiritual theme probably from the 1930s at the end of this collection.

.

.  .

.

untitled about 1930; untitled (cats) 1934; Girls in Blue 1933

.

.  .

.

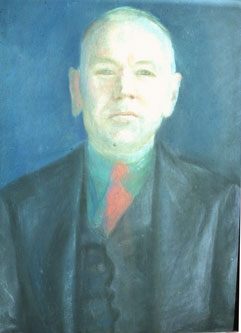

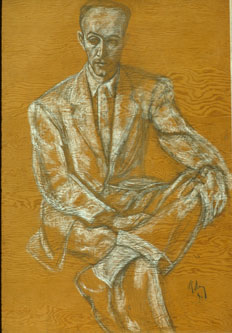

Reclining Nude 1938; John Bosch 1938; Everyman 1939

.

.  .

.

Market Man 1940; Red Tree of the Martyr 1940 §; Coliseum 1942

.

.  .

.

Concourse 1943; Space Architecture 1943; Portrait of Pehr Hallsten 1944 §

.

.  .

.

Portrait of Kenneth Callihan 1944; Scarred Torso 1945; The New Day ca. 1945

.

.  .

.

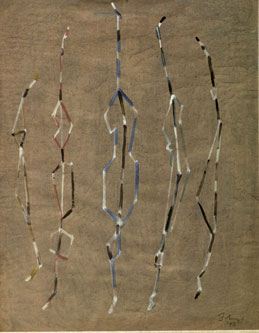

Day of the Martyr 1947; Five Dancers 1947; Biography 1948

.

.  .

.

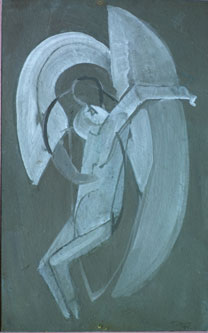

Enclosed Garden 1948; Jacob and the Angel 1949; untitled (animal sketches) 1949 §

.

.  .

.

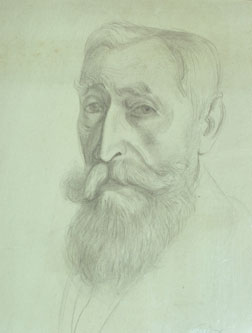

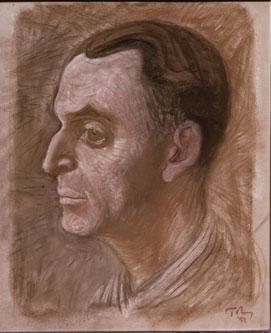

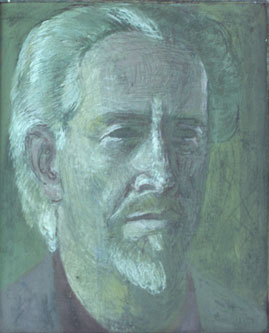

The Seekers 1950; Portrait of Otto 1952; Self Portrait 1952

.

.  .

.

Emerald Hill of Faithfulness 1952; New Crescent 1953; Carnival 1954

.

.  .

.

Wing 1954; City Notated 1954; Animal Kingdom 1954

.

.  .

.

Indian Landscape 1954; Sun and Clouds 1954; Saints and Windows 1954

.

.  .

.

Resurrection 1954; New World Dimensions I 1954; New World Dimensions II 1954

.

.  .

.

New World Dimensions III 1954; New World Dimensions IV 1954; Meditative Series No. VIII 1954

.

.  .

.

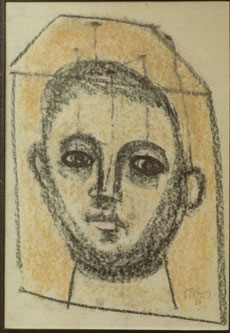

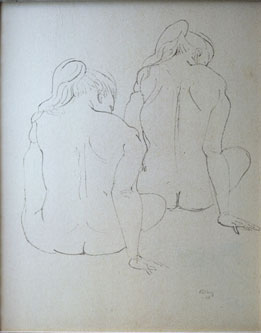

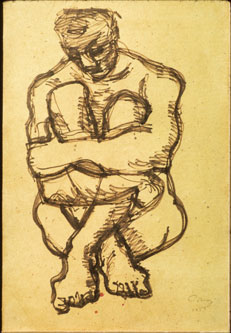

Head of Boy 1955; Two Seated Figures 1955; Seated Torso 1955

.

.  .

.

Christmas Greeting 1955 §; Hands and Feet 1956 §; Forest Fire 1956

.

.  .

.

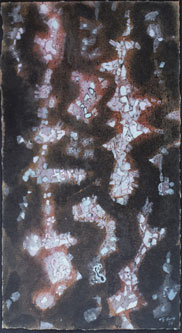

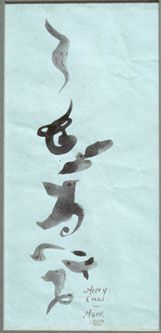

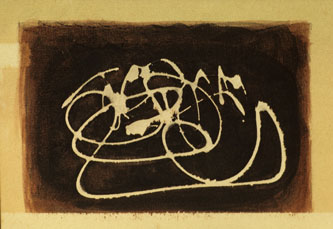

Untitled Sumi painting1 1957; untitled Sumi painting2 1957; Sumi VI 1957

.

.  .

.

Sumi IX 1957; Fire Dancers 1957; untitled Sumi with colored ink 1957

.

.  .

.

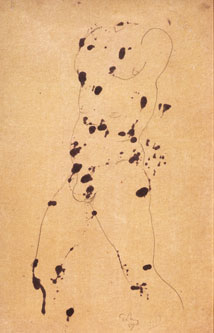

Sumi Flower 1957; Man's Torso with Spots 1957; Sleep 1957

.

.  .

.

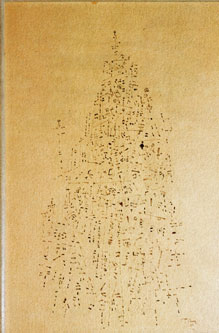

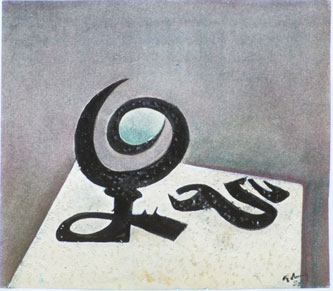

Chinese Grocery 1957; Calligraphic Still Life No. 3 1958; Sentinels of the field 1958

.

.  .

.

Jeweled Jungle 1958; Genesis 1958; Farmer's Market 1958

.

.  .

.

Two Dogs 1958; Pierced Sky 1958; Agitated Field 1959

.

.  .

.

Descent 1959; Traffic 1959; Eastern Calligraphy (Sumi) 1959

.

.  .

.

Baroque 1960; Little Sun 1960; Ancient Battle 1960

.

.  .

.

Ancient Mirror 1960; Minute World 1960; Lovers of Light 1960 §

.

.  .

.

Little World No. 40 1961; Journey 1961; Mountain Meadow 1961

.

.  .

.

Mono Prints No. 1 and 2 1961; HC VIII 1961

.

.  .

.

Christmas Card 1962 §; Configurations in Transit 1963; Fastnacht 1963

.

.  .

.

Burst of Spring 1964; Urban Renewal 1964 §; Christmas Greeting 1964 with letter on back §

.

.  .

.

No Space Left 1965; Oriental 1965; Other Places, Other Spaces 1967

.

.  .

.

Aerial Centers 1967 §; untitled monotype 1968; untitled monoprint 1968

.

.  .

.

Monoprint 1968; Monotype To Joyce and Arthur 1968 §; untitled (brown calligraphy) 1968

.

.  .

.

Untitled monotype 1969; monotype 1970; untitled 1969 §

.

.  .

.

Untitled (dog) very small 1970 §; untitled (man) very small, no date §; untitled 1930s §

The Dahl collection also includes a portfolio of prints of 28 pen drawings on wet paper made by Mark Tobey at Dartington Hall, England, in 1931-1932 §.

.

.  .

.

Signature on the cover; title page and dedication; pen drawings on wet paper

Click on the paintings to see a larger version

These are my own photographs of the original paintings, so the quality is not very good.

Copyright (c) by Arthur Lyon Dahl, all rights reserved

Page last updated 28 January 2023