Life in the forest is a complete break from life in the city, and a chance to renew an intimate contact with nature that is very important for me. There is always something to do around the chalet. What I do usually depends on the weather, the season, the condition of the garden, and priorities like dealing with a fallen tree or repairing the track up to my chalet after a heavy rain. The condition of the soil is important, being sometimes too wet or dry for digging, weed pulling, road or trail work.

I need some constructive physical activity as a break from the more mental activity involved in my professional activities, but could never do exercise for its own sake in a gym. While working around the chalet is not quite the seven labours of Hercules, it does force me to get regular exercise at no expense and in a much more agreeable environment. I am also trying to use manual tools more often to save fossil fuel and electricity. I usually alternate some reading or writing with a few hours of garden work. There are more pictures on the results of my activities in building forest trails, clearing fallen trees, and providing access to the different parts of my property on the page about my life at Brameloup.

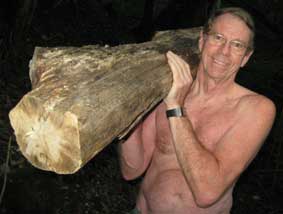

As explained on the page about my efforts to live a sustainable lifestyle, I try to save the energy and water consumed in washing clothes by wearing as little as possible when doing dirty work in the garden. I am easier to wash than any clothing would be, and while working I do not need clothing for warmth even in mid-winter. This is also a good way to burn more calories.

MY SEVEN LABOURS

Gardening

Mowing lawns and meadows

Trail making

Track maintenance

Chalet maintenance and improvements

Managing the forest and meadow ecosystem

Firewood

Building a stock of firewood adequate to heat the chalet through the winter is a year-round activity. I produce all the wood I need from my own forest. Most of this comes from fallen trees and branches, or from young trees, mostly fast-growing ash and many now dead from ash dieback, that need to be thinned or removed from areas that I want to plant to other things.

.

.  .

.

.

.

If there are fallen trees, I cut up the trunks with a handsaw or chainsaw, haul the wood up to the chalet, split the logs with either my hydraulic wood splitter (which my doctor recommended to prevent tendonitis), a sledgehammer and wedge, or an axe, depending on the kind of wood and the size of the logs, and stack it in the woodshed to dry.

Along the lower boundary of my property, many ash trees regrew in an abandoned pasture, and most started dying a few years ago from ash dieback disease from China now spreading across Europe. Quite a few fell in 2020, creating a puzzle of tree trunks that will be difficult to clear, with many suspended in the air out of reach.

.

.  .

.

Many fallen ash trees on my lower boundary in 2020

I found a special handsaw for timber that is almost as fast as a chainsaw, is easy to carry to less accessible places, and can be used even in the rain. It is both more ecological, and gives me good exercise. I have cut up several fallen trees with it.

.

.

.

.

Even large oak logs can be cut effectively with a hand saw

.

.

Different kinds of handsaws are useful depending on the circumstance and kind of wood

.

.  .

.

Cutting up trees with a chainsaw. Some trees are too big for a handsaw.

.

.  .

.

Hauling logs up to the chalet

.

.  .

.  .

.

Photos by Nabil Stendardo

.

.  .

.

Hauling wood is a year-round activity, and an excellent way to keep warm

.

.  .

.

Splitting logs with the hydraulic splitter

.

.

.

.  .

.

Splitting logs with an ax, or wedge and sledgehammer

I dig the smaller trees out by the roots, and then cut the thinner trunks and branches with big shears into the right length for my stoves.

.

.  .

.

Nabil Stendardo sometimes comes to spend a weekend with me at the chalet. Here he is helping me to cut up small trees for kindling.

To make adequate covered storage for firewood, I first converted the abandoned truck into a lawnmower garage and woodshed, and then built a larger woodshed near the chalet. Since green wood can take 18 months to dry, I need at least a 2 year wood supply.

.

.  .

.

Woodshed and tractor-mower garage converted from an old truck

.

.  .

.

New woodshed

.

.

By 2014, the woodshed was almost full; in 2019 I filled it thanks to 3 fallen trees in the forest

I also stack firewood under the eaves on both sides of the chalet, where it is accessible even in inclement weather.

.

.  .

.

Cutting and stacking a wood supply along the sides of the chalet

Gardening

I mostly try just to manage nature in my forest and meadows, with a little landscaping around the chalet with things that require low-maintenance, trying different plants to see what survives in my local forest ecosystem. Directly outside my bedroom window is a small garden of Japanese inspiration with stones, ferns, a dwarf maple, azaleas and some small bamboo. There are also spring bulbs, tulips and narcissus that I bought, and lilies transplanted from my forest. Some of the ferns are also local. I am adding more local flowers, like an orchid transplanted from the middle of the lawn where it would not have survived the traffic and mowing. For ground cover, there is the ubiquitous local ivy and Ajuga with its spikes of blue flowers. Interestingly, Ajuga was the ground cover our landscape architect used in our garden in California when I was a teenager.

I mostly try just to manage nature in my forest and meadows, with a little landscaping around the chalet with things that require low-maintenance, trying different plants to see what survives in my local forest ecosystem. Directly outside my bedroom window is a small garden of Japanese inspiration with stones, ferns, a dwarf maple, azaleas and some small bamboo. There are also spring bulbs, tulips and narcissus that I bought, and lilies transplanted from my forest. Some of the ferns are also local. I am adding more local flowers, like an orchid transplanted from the middle of the lawn where it would not have survived the traffic and mowing. For ground cover, there is the ubiquitous local ivy and Ajuga with its spikes of blue flowers. Interestingly, Ajuga was the ground cover our landscape architect used in our garden in California when I was a teenager.

.

.

Between the balcony and the road I have planted two hedgerows. I tried boxwood but it died of caterpillar infestation, and a few rhododendrons did well until the drought in 2022. There is another Japanese dwarf maple. There are a few roses struggling, as well as a wild rose.

In 2016, the boxwoods in my hedges were attached by the invasive boxwood caterpillar, completely defoliating several of them. I cut off all the infected parts of the plants, and they started to grow back in 2017. The caterpillars then spread to two boxwoods by my water tank, and in 2017, began attacking the large boxwood trees in front of my chalet, as well as the young regenerating leaves. By 2018, all the boxwoods were dead and I had to remove them.

Boxwood half defoliated by caterpillars

VEGETABLE GARDEN

In 2007 I started to make a vegetable garden to grow some of my own food, but this requires improving the soil. I compost all my organic waste, ashes and garden cuttings (Compost pile, right -->). When good soil from the forest washes onto the path to my chalet, I collect it and haul it to my garden. By 2008 a first section was ready. My first two attempts at planting seeds were mostly a failure. Only the potatoes, onions and a few zucchini and string beans survived until summer. After every rain a hoard of slugs emerges from the forest and heads for my vegetables, removing everything down to soil level. I do not want to use poison, and am not at the chalet often enough for mechanical elimination (giving them the boot). The other problem is watering and weeding in summer since I travel so much. In 2010, I installed a rainwater collection system on the nearby woodshed, with a 300 litre tank and drip irrigation, to provide some water during the summer. In 2012 I extended the system and added an automatic timer. I expected a reasonable harvest of potatoes, and some jerusalem artichokes and raspberries. However, gophers moved in and devoured almost everything. So before planting in 2013, I dug trenches around those parts of the vegetable garden not protected by concrete foundations, and buried a wire grill to half a meter depth.

In 2007 I started to make a vegetable garden to grow some of my own food, but this requires improving the soil. I compost all my organic waste, ashes and garden cuttings (Compost pile, right -->). When good soil from the forest washes onto the path to my chalet, I collect it and haul it to my garden. By 2008 a first section was ready. My first two attempts at planting seeds were mostly a failure. Only the potatoes, onions and a few zucchini and string beans survived until summer. After every rain a hoard of slugs emerges from the forest and heads for my vegetables, removing everything down to soil level. I do not want to use poison, and am not at the chalet often enough for mechanical elimination (giving them the boot). The other problem is watering and weeding in summer since I travel so much. In 2010, I installed a rainwater collection system on the nearby woodshed, with a 300 litre tank and drip irrigation, to provide some water during the summer. In 2012 I extended the system and added an automatic timer. I expected a reasonable harvest of potatoes, and some jerusalem artichokes and raspberries. However, gophers moved in and devoured almost everything. So before planting in 2013, I dug trenches around those parts of the vegetable garden not protected by concrete foundations, and buried a wire grill to half a meter depth.

.

.  .

.

The old truck next to the vegetable garden converted as a tractor-mower garage, wood storage and rainwater catchment from the roof.

Rainwater catchment on the roof of the shed to supply drip irrigation of summer vegetables, with automatic timer

2008

.

.

Vegetable garden after the first harvest in 2008. Jerusalem artichokes (Topinambour)

.

.  .

.

The first year's harvest (2008)

2009

.

.  .

.

Vegetable garden at planting, in summer, and rather poor harvest in 2009 due to drought

2010

.

.  .

.

2010 vegetable garden; only the potatoes, onions and jerusalem artichokes came up. The slugs did not give the other vegetables a chance. I did harvest about 8 kg of potatoes.

2011 - a good year

.

.  .

.

Digging up potatoes in 2011. The harvest fed me the whole winter, and I still had lots of potatoes to plant in the spring

2012 - the gophers won

.

.

Planting in the spring; the poor harvest in the fall (right). The pile of jerusalem artichokes at left, and half the potatoes, were collected by the gopher for its winter store.

With more improved soil and compost, in 2012 I planted the whole 20 square meter garden to potatoes and jerusalem artichokes, and while the plants grew well through the spring, the summer was bad in 2012 for potatoes, and a gopher systematically removed everything else. Most remaining potatoes (right) were between pea and marble in size, and only two jerusalem artichokes remained from at least 50 plants, apart from those stored by the gopher. I have now buried a metal screen across the ends of the garden to try to keep the gophers out. I did not know that gophers existed in Europe (they have no common name in French), but having found one dead the previous winter (see Nature page), and now finding the damage in my garden, they must be here.

2013

.

.  .

.

Vegetable garden in spring 2013, ready to install the last section of underground screening; potatoes in July, in flower.

.

.

Harvesting potatoes in November 2013. The gophers did not get in, and the harvest was quite good.

.

.

Having finally found a variety of raspberry that thrives under my conditions, I had a good harvest in 2013

2014

.

.  .

.

The potatoes grew well in the spring of 2014, and there was a first spring crop of raspberries, another in summer and more in the fall, but the rainy summer kept the slugs active, and the potatoes suffered some kind of rot. I found many potato skins, but only a few small potatoes.The jerusalem artichokes bloomed in September, and produced a better crop than the potatoes, but something (birds or dormice?) devoured 17 and 2/2 of my 19 peaches. Not a very good year.

2015 - 2016 - 2017 - 2018 - 2019

.

.  .

.

In 2015, I again planted potatoes and jerusalem artichokes saved from last year's harvest. The potato harvest was reasonable but the potatoes were small. The jerusalem artichokes did better. There were raspberries all summer and fall. In 2016, the potatoes did not grow well, and I could not harvest anything because of my hip replacement operation. In 2017, I replanted potatoes, and the jerusalem artichokes resprouted in abundance. I only harvested a quarter of the garden because the potatoes were the size of marbles. In 2018 (right), I replanted the tiny potatoes, but only one plant survived until summer. There are more jerusalem artichokes, but the plants are smaller than usual. My automatic watering system has not been working.

I had no time to plant anything in 2019, but the jerusalem artichokes take care of themselves, and raspberries are welcome invaders.

2020

In 2020, the pandemic closed the border between Switzerland and France, and no spring gardening was possible. When I was finally able to return at the end of June, everything was overgrown. One surprise was that something had just devoured my entire peach tree, leaving only a gnawed stump with even the bark freshly peeled off. I do not know what would eat an entire tree, leaves, branches and trunk, without leaving a trace, not even a single leaf behind.

.

.  .

.

The stump of the peach tree, freshly devoured; details of gnaw marks a month later

In 2022, the same thing happened to a pear tree that I had planted alongside my lower meadow. Most of the tree was gone, leaving a gnawed trunk and some lower branches.

Gnawed stump and lower branches of a pear tree

IMPROVING THE SOIL

The soil immediately around my chalet is a man-made platform leveled to construct the chalet on sloping land (although terraces continuing along the hillside in the forest suggest that there may have been vineyards or other plantings in earlier centuries). There is thus no topsoil, and I have to add good soil and compost to the vegetable garden regularly to try to improve it. One of the best sources of soil is the track just above my chalet, where soil eroded from the forest collects in a depression at Brameloup stream. By carrying it away, I both remove slippery mud from the track and add to my vegetable garden.

Hauling soil from the track (left background) for my vegetable garden

Hauling soil from the track (left background) for my vegetable garden

PLANTING

I am gradually adding fruit trees at the end of the garden and alongside the meadows, including several varieties of apple (to accompany two wild apple trees), pears, apricots, peaches, plums and meribelles. Some of the trees are traditional local varieties adapted to Savoie. Unfortunately the deer like to strip the bark off the young trees in winter. There is already a big wild cherry tree, but with small cherries, probably sprouted from someone's cherrystone. My raspberries are finally starting to produce, and are spreading naturally. There are wild strawberries (few but delicious) and the terrible blackberries everywhere, with fruit too small to be worth all the problems they cause.

.

.  .

.

Planting fruit trees and rhododendrons

Apart from that, I simply try to manage nature, encouraging what I like and trying to maintain a variety of habitats and landscapes. I am increasingly replacing imported plants with local ferns, orchids and lilies in the garden around my house.

WEEDING

In fact, most of my gardening is not planting new things, but the constant battle against those things I do not want. Nature always tries to re-establish its supremacy and restore the original forest, starting with weeds and fast-growing species that encroach on the cleared areas. The worst are the wild blackberry brambles of several kinds which have tough roots that regenerate, lots of vicious thorns, and long runners that root wherever they touch the ground. When I bought the chalet, the cleared area around it was overgrown with dense thorny blackberry thickets, a meter or more high. To reconquer a bit of garden, I have to remove all the brambles, root them out completely, and return several times over a couple of years to again root out new sprouts.

.

.  .

.

Uprooting blackberry brambles and burning them; a newly cleared section of garden, formerly a thicket of small trees

Then there are the tree seedlings, mostly ash, oak and maple, that appear every year by the thousands in the garden and all through the forest. Smaller ones can usually be pulled up if the soil is wet, but larger trees have to be chopped out at the roots. Any broken stem or stump will grow back more tenaciously than ever. There are just so many of them that it is impossible to keep up. Most other weeds are manageable if I take a little time.

.

.

Pulling tree seedlings by the hundreds

CLEARING OVERGROWTH

.

.  .

.

Removing saplings by uprooting them, cutting the roots as necessary

.

.  .

.

The leaves and small branches I cut up for compost or burning, while the trunks, if they are large enough, are dried and cut up for firewood.

In May 2009, my Dutch intern, Lieuwe Vinkhuyzen, helped me to clear a new section of dense trees, brambles and vines beyond the vegetable garden so that I could plant more fruit trees. He was able to uproot some quite large trees.

.

.

.

.  .

.

cleared area in July 2009

Mowing lawns and meadows

Mowing the lawns around the chalet and the meadows down the hill keeps the weeds and seedlings back. I have never planted grass, so the lawn is just whatever survives the cutting. There is a ring of "lawn" around the chalet, including the entrance, and a large flat lawn beyond the chalet towards the truck woodshed and the orchard and vegetable garden (see Life at Bramloup). It has a fire circle in the middle for burning uncompostable garden debris. I mow about 800 square meters regularly.

.

.  .

.

Lawn between the chalet and the vegetable garden, and down to the entrance on the rural track through my property; upper boundary just mowed

.

.

The upper meadow before mowing, and mown in mid-summer

To encourage the meadow wildflowers, I only mow the meadows down the slope and across the road one or two times a year: in mid-summer after the spring orchids have withered but before the autumn lilies bloom, and if necessary in early spring or in the fall after all the flowers have bloomed and withered. When the grass is high I have to use my old tractor mower, inherited from Martine's house in Belgium, although I am now trying to replace it with a scythe as much as possible and find that ancient implement very efficient. For the 800 m2 of lawn immediately around the chalet, I generally cut it with a push mower, which is more ecological. After a good mow, everything looks neat and tidy. It is the easiest way to keep part of the garden civilized.

.

.  .

.

Ecological lawn mowing (less greenhouse gas emissions than sheep or goats)

.

.

Mowing, and sweeping up after

.

.  .

.

Mowing tall grass in the meadow with a sythe in mid-summer

.

.  .

.

The old tractor mower, which I use as little as possible, only when the grass is too high and dense for hand mowing

In 2020, the frontier with Switzerland was closed for three months from mid-March to mid-June during the pandemic. When I finally returned, vines had overgrown the chalet and grass was high on the lawns and meadows. It took several days of pruning and mowing to bring things back to normal.

.

.  .

.

Chalet overgrown on 30 June 2020; a month later after pruning and mowing

Trail-making

One of my favorite pass-times since I was a teenager is making trails through the forest. One reason I bought the chalet was because it had lots of land in the forest for trail-making. There is the long area of sloping forest beyond the chalet and above the lower pasture, and the steep ravine between the rural track and the watercourse of the Brameloup (an intermittent streamlet in the winter). Since most of my land slopes steeply, I have had to build trails to make the different parts accessible, reaching every part of it by 2017. The trails also have to be cleared of fallen branches and leaves, and repaired from time to time. This is best done when the ground is damp but not too wet, so that the earth and stones can be consolidated on the slopes. The best tool for this was a US army surplus trenching shovel. My parents gave me one after WWII dated 1942, and while I had to replace most parts of it, I used it for 60 years until it finally broke from metal fatigue in 2007. Fortunately I found a nearly comparable Swiss army shovel in a military surplus sale. The trails provide access to firewood, to enjoy the changing nature in different seasons, to take walks and observe the wildlife.

.

.  .

.

Trail building

.

.  .

.

Clearing a trail in winter

In early 2012, I built a new trail down the steep ravine of the Brameloup Stream on the eastern boundary of my property, filled with some of the largest and tallest trees on my property. See also life at Brameloup.

.

.  .

.

The trail down the Brameloup ravine; bottom of the ravine with dry stream bed

.

.  .

.

The large trees in the ravine

In the fall of 2014, I laid out another trail along the upper slope of the ravine. The soil was so steep and unstable that I had to lay tree trunks between standing trees to provide support for the path. It was quite an engineering challenge.

.

.  .

.

New trail along the upper ravine branching from the lower ravine trail; trail at the top of the slope; between the trees

.

.  .

.

Building the upper trail across a steep section with horizontal tree trunks braced against trees

.

.  .

.

The ravine slope was too steep for the trail to pass without tree trunks and large rocks for support

.

.

The new trail along the edge of the ravine towards the lower meadow in summer and winter

Having developed the technique for steep slopes, I could now build a trail down the ravine in the bottom corner of my property, using tree trunks that I cut in the vicinity and braced between trees and stumps. Without these, I could not even work on the steep slope, more than 45° in some places, and I slid down more than once. By January 2015, I was most of the way down after four switchbacks, and by the end of January had reached the stream bottom with three more switchbacks and some steps. The temperature was 2-4°C but the work kept me warm. February was rainy and the mud was too slippery to work. In March, the ground was dry enough to continue working on a circuit along the bottom slope of the ravine, to connect with the train down the ravine built in 2012.

.

.  .

.

Starting to build the new trail down; looking down the steep slope from the top; first switchback of the trail under construction

.

.  .

.

Start of the new trail down; the first switchback with supporting tree trunk; me working on the first switchback

Second and third switchbacks; me working on the second switchback; stairs on the second switchback, and third switchback

.

.  .

.

Looking down at the third and fourth switchbacks; me working on the third switchback; starting the fourth switchback

.

.  .

.

Four switchbacks seen from the bottom; looking down before building the trail to the bottom; constructing the trail at the end of the fifth switchback

.

.  .

.

Sixth and seventh switchbacks to the bottom of the ravine; end of the trail alongside the stream; cutting low branches while hanging from a tree on the steep slippery slope

.

.  .

.

Lower part of switchback 5 to the large tree; switchbacks 6 & 7 around the tree to the bottom; without overhead branches, it is impossible to stand on the 45° muddy slope where the next section of trail needed to be built behind me

.

.  .

.

Looking up at switchbacks 5, 4, 3, & 2; trace for the trail up the ravine on the right, with tree trunk to be moved into place; balancing on the steep slope

To complete the trail, I needed to lay tree trunks along the ravine slope to connect the trails at the upper and lower ends of the ravine. The slope is steep and with only one stump and one tree as support along 15 meters, so this had to wait for drier weather. In the meantime, I started in January extending the trail down from the upper part of the ravine, where I had already made a trail in 2012, to the one tree along the slope. I had to use very long tree trunks to span the steep slope with only one stump mid-way along, in order to connect to the trail from the lower ravine. Fortunately there were several trees that had fallen horizontally across the ravine that I could use for this.

.

.

Starting construction of the new trail; the first section of new trail from the upper ravine to the one available tree (which later broke and fell)

In March 2015, conditions were perfect for trail construction, with the soil damp but not slippery. In two afternoons, I laid a tree trunk along the slope to the one stump at mid-point, and built the trail to the stump. Fortunately, the curves in the tree trunk nearly matched the curves in the slope, dipping under a horizontal tree. Then I cut another tree fallen across the ravine, both to clear the way for the trail, and to provide a 5.6 meter log to bridge the last remaining gap in the trail.

.

.  .

.

Looking down at the new section of trail; the trail along the slope to the stump; me on the new trail, with one fallen tree to duck under

.

.  .

.

The trail up the ravine to the stump; stakes driven in to support the log; me on the new section of trail

.

.  .

.

The end of the middle new trail section at the stump; looking beyond the stump to where the upper trail ends; the 5.6 meter log cut to bridge the gap (it was too short)

Completing the trail in late March presented a number of challenges. The one tree on the upper section that I had counted on to support the horizontal logs broke off at the roots since I started building the trail in January and leaned dangerously, so I could no longer count on it for support. Fortunately I had not yet nailed the first log to the tree. Then the tree that I had cut (above right) to bridge the gap was too short. I had to add a third log and to drive stakes all along the three logs to anchor them against the slope, all while using the logs themselves as support to keep from sliding down the slope.

.

.  .

.

The unstable tree broken at the roots; the new sections of trail hugging the steep slope, with logs held by stakes

.

.  .

.

The new trail above the stream bottom; the trail up the ravine; me on the completed trail

.

.  .

.

In the fall of 2015, another big tree fell across the trail but did not block it until 2016, so in 2017 I cut it up with some difficulty; another smaller tree was easier

In the fall of 2015, I started building another trail at the far west end of my property, to loop down to the lower corner that had previously been inaccessible. Using the same technique of supporting tree trunks, I started laying the steepest sections, but the soil was too dry to cut the trails, so I had to wait for winter and more rain to continue. In late January 2016, conditions were finally right, with the soil neither too wet nor too dry, so I was able to complete the loop of trail.

.

.  .

.

Start of trail construction in the lower western corner of my property; me on the completed trail

.

.

Start of the new trail down the slope; trail along the lower property line

.

.

Last section of new trail up the slope

My last big trail project in 2017 was to add an upper trail through the western forest along the top boundary of my land, where there are some very large trees. At the western end, there was a tree with large roots on a very steep slope, so I had to build a ramp with fallen logs crossing the roots and down along my western boundary. It took a few weeks to clear and level 80 meters of trail along the slope.

.

.  .

.  .

.

Middle trail at the start of the new upper trail before construction; the intersection under construction; the finished trail; regrading the middle trail before the intersection

.

.  .

.

Clearing the track for the new upper trail

.

.  .

.

Before and after constructing the trail; some sections required large stones as support on the steep slope

.

.  .

.

The alignment before starting; me constructing the trail

.

.  .

.

A large tree on the upper boundary; me extending the trail; a finished section of the upper trail

.

.  .

.

Before and after cutting the trail around the tree

.

.  .

.

The trail beyond the large tree, before and after

.

.  .

.

Building the trail between the large tree and the western boundary

.

.  .

.

Supporting logs for the ramp crossing the tree roots and descending to the property line

.

.  .

.

The ramp, before and after filling it in with soil

.

.  .

.

Laying logs for the ramp, and the completed ramp down

.

. The ramp down

.

.  .

.

Connecting the upper trail to the middle trail, before and after, looking up and down

In late 2017, I decided to add a trail connecting the middle and lower trails in the western forest, running diagonally through the large central area of trees and ivy ground cover where the slope was not too great. In the middle of construction, a wild boar came in the night and dug up much of the newly graded trail, leaving footprints behind (see nature)

.

.  .

.

First part of new trail forking to the right; before trail construction; ivy cleared but trail not yet cut

.

.  .

.

Start of new trail; trace of the trail through the forest; completed trail after repairing damage by the wild boar

.

.  .

.

Trail under construction; completed trail

In January 2023, a windstorm blew down a large dead oak tree above my property, and in falling it knocked down three large living oak trees completely blocking my land (see my life at the chalet page). Building a new trail around the stumps became an opportunity to start restoring all of my trails after years of neglect during the pandemic.

.

.  .

.

Fallen trees across the upper trail; across middle trail; middle trail completely blocked

.

.  .

.

Stumps of fallen trees; rebuilt upper trail around stumps

.

.  .

.

New trail around stumps; rebuilt upper trail

The next challenge was to clear many fallen trees, both from extreme windstorms and ash trees killed by disease. Another large hundred-year-old living oak fell across the far end of my garden in February, blocking the trail down into the forest.

.

.  .

.

Fallen oak tree now cut

Then there were the many trees criss-crossing my lower trail, which I finally cleared by the time of my grandchildren's visit in July 2023.

Many fallen trees in lower forest

.

.  .

.

Lower trail cleared of fallen trees

Track (road) maintenance

The last 1 1/2 kilometers of "road" to my chalet is an unpaved rural track which is a public right-of-way (although motor vehicles are now prohibited) and should normally be maintained by the local municipality. It was originally used by the farmer at Signy around the hill a kilometer beyond the chalet to take his milk to the village. However, since the track to my chalet crosses the land of three municipalities in distant villages, and I am now the only one who lives on it, it is usually neglected. The village of Frangy did put some gravel down once on a particularly muddy stretch of the lower track, but the only time a maintenance crew came all along it was when they prepared it for a cross-country bicycle race. They do mow the grass and cut back the bushes along the sides of the first kilometer once every year or so as part of the highway maintenance. Nothing is done for the last 400 meters up the slope to my chalet, so I am the only one to maintain it.

The first kilometer is more-or-less gravelled track along a maize (corn) field and following the other side of the fence from the highway bypass. It dips steeply for the two underpasses under the highway (see Frangy). Some parts have lots of loose stones and gravel.

Track along the highway that is the main access to the chalet

Then the track climbs up through the forest to the chalet, passing a small pasture which was used by the farmer at the top of the hill in Quincy who rents the Signy Farm pastures, and crossing the middle of my property, running near to the chalet. The track then continues up to the old farm at Signy (now blocked by fences), with a branch going steeply up the hill to the farms and village of Quincy on the plateau.

.

.  .

.

Track up the hill to the chalet; lower track with fallen trees; track crossing my property

The lower track is now prohibited to all motorized traffic, except for those like me who need to access their property, but some motor-bikers and quads still use it. The track is normally reserved for hikers, horseback riders and trail bikers, and even the occasional trail bike competition. It is an official departmental bike route. The track up the forest slope is just soil with nothing to stabilize it, so it becomes muddy and slippery when wet, and erodes rapidly in heavy rain. I have cleared fallen trees, constructed and maintained drainage channels to control erosion, and added gravel from a glacial deposit on my property, wheelbarrow by wheelbarrow, shovel by shovel. Over time I have managed to stabilize much of the lower track so that I can drive up it reasonably safely, although there have been some difficult times in the early years and recently after a rainstorm followed by a heavy snowfall when I got stuck on the way up. Each time I have a problem, I make another improvement. In 2008 the track was blocked four times by fallen trees or large branches. I now carry a saw in my car to clear any fallen trees that block my way.

.

.  .

.

Collecting gravel from my little quarry

.

.  .

.

Stabilizing the track with gravel

The upper path from the chalet to Signy Farm is blocked at the farm by locked gates, and the branch up to Quincy is too steep and eroded for most vehicles. One part runs through a thick clay deposit kept wet by a spring in winter. In wet weather even all-terrain vehicles get stuck in the mud. If it stays cold for very long, the water seeping onto the track forms a thick layer of ice, making the track impracticable for everything. I have made an alternative path through the forest, which was used for the official Musièges Trail 24 km footrace in 2019 (see my life in Brameloup).

.

.  .

.

The track up the hill from the chalet goes straight to Signy farm and right up to Quincy. I have installed signs

.

.  .

. .

.

Steep track up to Quincy through muddy clay. I have tried to stabilize the worst sections with stones and rubble. There is a spring that seeps into the clay.

Track iced up in the winter with water from the spring

In early 2008 a very large tree (70 cm in diameter) fell across the upper track just at the worst spot, blocking it completely so even pedestrians could no longer pass. I first made a detour through the forest for hikers and horses, until a farmer whose daughter rides horses came and cut out the middle section, leaving the trunk in the track but making space for horses and trail bikes to pass. It took me over a year to gradually cut up the fallen tree for firewood. It provided enough wood to heat me for two winters, although the wood was not very good quality.

.

.  Cut up fallen tree

Cut up fallen tree

I first cut the log most of the way through with a chain saw, but my chain saw was too short, so I had to finish cutting with a hand saw and then pry the sections apart. Fortunately it was not too hard to roll the disks down the hill to my chalet, as they were too heavy to carry.

.

.  Cutting the log into disks

Cutting the log into disks

.

.  .

.  Cut up log

Cut up log

Then I had to split the disks with a wedge into pieces small enough for my wood splitter

.

.  .

.

In early 2010, another large dead tree fell in the same place, blocking the track again. I made a little space to get around it at first. In summer, a crew removed enough of the tree for vehicles to get by, and I cut up the rest for firewood in the fall.

.

.  .

.

The second fallen tree across the track

In Winter 2022, another tree fell across the track at breast height, completely blocking it until I could cut up and remove it.

Chalet maintenance and improvements

When I bought the chalet, it had been trashed and abandoned for several years. In restoring it, I have tried for energy efficiency and minimal use of water. The walls and the roof were still in reasonable condition, and it had electricity and telephone. I had to clean and redecorate the interior completely while adding storage space and shelving, replace most of the broken windows and hardware, upgrade and add electrical circuits, update the kitchen and change all the appliances, transform the fireplace into a wood heater and add supplementary electric heating, convert the bare attic into two bedrooms, insulate the roof and the whole exterior of the chalet, reinforce the security, and replace the outside balcony. Many of the materials used were recycled. There was supposed to be a connection to the local water system, but it took 2 years to get reconnected (see the water saga). I had to rebuild the septic tank which had caved in, restore the drainage, add a new pumping system and line the water tank with fiberglass. In 2008 I completed a switching system for automatic filling of the water tank, and replaced the overhead wiring for the water pump with an underground conduit. Most of what needed to be done has now been done, and the chalet is now quite comfortable year round. By 2013, the roof was rotten and leaking, and had reached the end of its life, so after a first contractor had gone bankrupt, I found an excellent local contractor who replaced the whole roof and doubled the insulation in 8 days. This was the only job beyond my do-it-yourself capabilities. The tile floor in the living room could also be changed, since some tiles are broken, as could the ugly purple bathroom sink, but these are not urgent. Now I can spend more time on things outside.

.

.  .

.

Insulating, cementing and painting the exterior

.

.  .

.

Reinforcing shutters; installing shelf brackets

.

.

Installing shelves in the chalet

.

.  .

.  Woodshed

Woodshed

Building the new woodshed with wood recycled from the abandoned chalet on my property

.

.  .

.

Other regular maintenance includes cleaning the gutters and sweeping the chimney; in 2019 I replaced the roofing on the toolshed and woodshed.

REPLACING THE ROOF

It took only 8 days in October 2013 for two workers to remove the old roof, double the rafters and insulation, and lay a new tile roof, and two more days for me to put a first coat of stain on all the exterior woodwork of the eaves, and finish the interior around the roof windows. Work was completed just before the autumn rains.

.

.  .

.

The workers set up scaffolding and removed the old roofing of tar-paper shingles on particle board

.

.  .

.

Rotten rafters were replaced, new wood under-roofing laid above the eaves, and all the rafters doubled

.

.  .

.

14 cm of new insulation was added, a waterproof subroof laid, and the roof windows replaced

.

.  .

.

Cross-strips for the tiles were added, the new tiles laid, and the gutters replaced

.

.  .

.

The new roof, after I painted all the new woodwork under the eaves

WATER

Since the municipal water system is now supplied by a reservoir 20 meters lower than my chalet, I had to install a pump in the forest down the hill to pump water up to the storage tank at the top of my property (see also the water saga in My life at Brameloup). This required digging trenches through the forest to lay an underground conduit and electric cable, as well as a wire up to the tank for a floating switch. The original overhead wire through the trees failed in 2008 (some animal ate through the insulation and it shorted out), so I had to finish the last 50 m of trenching to complete the underground replacement.

.

.  .

.

Digging a trench is only half of the work. After the cables are laid, the trench has to be filled in again, the turf replaced and the earth packed down with a heavy tool for the purpose.

Packing down the newly filled trench

Packing down the newly filled trench

Water supply

.

.  .

.  .

.

Rebuilt water supply, with added fiberglass-lining in the storage tank which I roofed with tiles; control valves and floating switch in the tank; old water tank where the pump was originally; and new water pump down the hill in the forest.

.

.  .

.  .

.

The bathroom is equipped with a mini-tub and reduced flow shower with 3-jet pulsed head supplied by a 15 liter water heater, providing enough hot water for a comfortable 10 liter shower (or two in a stretch). Due to the gravity feed from the water tank, I had to add a pump (right) to provide enough pressure for the shower.

For the toilet, rainwater from the roof from a water trap in the downspout is siphoned automatically into a 100 liter tank over the bathtub.

Managing the forest/meadow ecosystem

With 8,717 square meters of land, I have quite a bit of forest and meadow to manage. The different parts of the property are quite different ecologically, with various mixes of forest trees and interesting wildflowers including different kinds of lilies and orchids (see the seasonal pages, the page on nature, and the page on life at Brameloup). My goal is to maintain the maximum habitat diversity while supplying enough wood for my heating needs and eventually producing at least part of my food. I am trying to time my mowing of the meadows to prevent the forest from growing back while preserving the right conditions for the orchids, lilies and other flora. Occasionally, it is necessary to clear along the sides of the meadows to keep the forest from encroaching. The badgers, foxes, hares, deer, martens, dormice and other wildlife that I have seen on the property can presumably take care of themselves, and as a botanist, I am more interested in the plants anyway. So I observe and intervene lightly, mostly by removing invasives like the brambles and excess ash seedlings. A newly invasive variety of bramble with many small thorns and stems that arch and root to spread, appeared in my forest in about 2010, and is now spreading everywhere. My trails give me the access I need to maintain and enjoy all the different areas.

With 8,717 square meters of land, I have quite a bit of forest and meadow to manage. The different parts of the property are quite different ecologically, with various mixes of forest trees and interesting wildflowers including different kinds of lilies and orchids (see the seasonal pages, the page on nature, and the page on life at Brameloup). My goal is to maintain the maximum habitat diversity while supplying enough wood for my heating needs and eventually producing at least part of my food. I am trying to time my mowing of the meadows to prevent the forest from growing back while preserving the right conditions for the orchids, lilies and other flora. Occasionally, it is necessary to clear along the sides of the meadows to keep the forest from encroaching. The badgers, foxes, hares, deer, martens, dormice and other wildlife that I have seen on the property can presumably take care of themselves, and as a botanist, I am more interested in the plants anyway. So I observe and intervene lightly, mostly by removing invasives like the brambles and excess ash seedlings. A newly invasive variety of bramble with many small thorns and stems that arch and root to spread, appeared in my forest in about 2010, and is now spreading everywhere. My trails give me the access I need to maintain and enjoy all the different areas.

.

.  .

.

Open forest at the far end of my property; newly cleared areas along the sides of the upper meadow.

CLEARING AN OLD DUMP

One problem that is now largely resolved was removing the dump in the steep ravine of the Brameloup stream between my property and Signy farm next door, which had been used by the farmer and the former chalet owner for years as a rubbish dump, including for 5 old automobiles (1 2CV, 2 Renault4, 1 Simca, 1 Opel). I removed more than 50 100-liter bags of rubbish to the recycling center, including hundreds of bottles. The cars I could only consolidate in one pile, and then cover them with branches to disguise them as something natural. Each year I add some more branches to keep the cars covered, and they are gradually disintegrating and being buried.

I learned something about the persistence of waste; some fabric and clothing in synthetic fibres that had been buried for 30 years was still wearable, such as the shorts below.

.

.  .

.

Five old cars in the stream bed hidden under branches

These shorts were buried in the dump for 30 years

These shorts were buried in the dump for 30 years