MaDePro India

For the third time I accompanied an EPFL (Ecole Polytechnique Fédéral de

Lausanne) course to India. The Certificate of Advanced Studies in Management

of Development Projects (MaDePro) brought together 24 participants from

almost as many countries: Bangladesh, Brazil, Cameroon, Canada, Colombia,

Costa Rica, Ethiopia, Haiti, Germany, Guatemala, Guinea Bissau, India,

Israel, Kyrgyz Republic, Mexico, Nepal, Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland.

After 6 months of distance learning, including my two-week module on

sustainable development, we gathered at the National Institute of

Advanced Studies in Bangalore, Karnataka State, India, for an introduction

to Indian culture and cross-cultural communication. We then went for a week

to the remote village of Channakeshavapura (CK Pura for short, 330

households), four hours from Bangalore, to live in the village as guests of

Sheshagiri Rao and his family. Sheshagiri is both a decendent of the founder

of the village 150 years ago, and an environmental scientist who went back

to his village to help his people. The participants in four groups

researched and prepared useful development project proposals on the impact

of migration on the village, sustainable use of groundwater, microcredit,

and the introduction of information technology into the local schools. This

was my third visit to the village (see 2010

and 2012) and we learned that two

projects from the last course had had a significant impact.

.

.

National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bangalore, where we stayed

before and after CK Pura

We happened to arrive in Bangalore on the Hindu festival of holi when they

throw coloured powders on everyone. Our participants began their immersion

in a culturally-appropriate way.

.

.

Participants after holi

.

.

Class in cross-cultural communication

As part of a day on urban development challenges, we made a field visit to

urban waste recycling schemes in Bangalore run by an association of former

rag-pickers. Instead of going through refuse dumps and roadside scrounging,

they have contracts with housing complexes and the municipality to collect

and sort waste for recycling in economically stable and sanitary conditions.

.

.  .

.

Preparing to leave NIAS for the field visit

.

.  .

.

A housing complex of 1,000 apartments where the tenants association

and the rag-pickers association collaborate to collect, sort and recycle

the wastes from the building

.

.  .

.

Modern composting machines; the housing complex

,

,

Yuri Changkakoti, the course coordinator from EPFL, and former

rag-pickers; a nearby building in Bangalore

.

.  .

.

A municipal district dry waste collection centre run by the

rag-pickers under contract

.

.

The association organizer, the manager of the centre and his team of

former rag-pickers in their uniforms and gloves

.

.  .

.

A second district dry-waste collection centre; participants with the

association organizer, the director of the centre (in violet), a former

rag-picker on the streets

.

.  .

.

An experimental machine for compacting packaging; employees sorting

wastes

.

.

Unsorted wastes; a experiment in recyling Tetra Pak packaging

On the way to the village of CK Pura,

we stopped at a natural medicines company farm that Sheshagiri has been

advising on sustainable agricultural practices in this semi-arid region. The

agroforestry approach combines trees for water retension, bunds to slow

run-off, composting to improve the soil, and holding ponds and borehole

recharge at the bottom of the slope.

.

.

At the company farm headquarters; initial explanation by Sheshagiri

Rao

.

.  .

.

The land has been contoured to slow run-off, with rows of trees,

bunds and pits to catch rainwater

.

.  .

.

Medicinal herbs are grown between the rows of trees, wider or

narrower depending on the soil and water

.

.  .

.

High-value trees with deep roots are combined with fast-growing trees

that can be cut back to save water in droughts

C.K. Pura

The village of Channakeshavapura is in a semi-arid region where groundnuts

(peanuts) have been the traditional cash crop, but rainfed agriculture is

risky, and the last three years have seen rainfall far below average. Water

from traditional wells and boreholes allows cultivation to continue for

those who can afford it, when the unreliable electricity permits. Women

supplement the family income by processing tamarind or rolling cigarettes.

There are some sheep and cows. There are both Hindus and Moslems, and some

low caste tribal shepherds nearby. Life is difficult. In most families,

someone has migrated to the town or city.

.

.

The gate in the former village fortifications; our hosts Sheshagiri

Rao and his wife, son and sister

.

.  .

.

Dr. Rao gives an initial briefing to participants in his home

.

.  .

.

An initial tour of the village shows the reality of village life

.

.  .

.

Local resource people provide information and answer questions; our

Nepalese participant covers up in the sun

.

.  .

.

Neem trees provide some shade

.

.  .

.

Women processing tamarind and oil nuts

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

A large tamarind tree; an abandoned house; stone fencing

.

.  .

.

Village streets

.

.  .

.

The village Hindu temple; a giant cart for the recently-completed

procession with the village goddess, held every 24 years

.

.

The goddess is still being moved from house to house

.

.  .

.

Procession with drums and the goddess

.

.  .

.

School children; a class under a tree in the school yard; the new

village water purification plant

.

.  .

.

The municipal government building; water tank; microcredit bank

.

.  .

.

A memorial to those who defended the village; cellphone towers;

villagers come to see us off

.

.  .

.

Village livestock; old and new forms of transport

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

Views of the village from the roof of Sheshagiri's house

The class was divided into four groups, each preparing a specific

development project: problems of groundwater management; evaluation of

microcredit schemes; introduction of information technology into the

schools; and the impacts of rural-urban migration on the village. The groups

visited the village and surroundings to collect background on their problems

and to interview people concerned, accompanied by a local resource person

and translator. They then had to come up with proposed solutions that could

be implemented to solve the problem.

We learned that two of the projects from the last class two years ago had

led to significant progress. A proposal to develop televeterinary medicine

for illiterate shepherds was about to be implemented after leading to a

similar cellphone application for farmers. Another project that had assessed

the problems with pump maintenance had stimulated the federal government to

select the district for a pilot project to replace all the pumps with new

robust energy-efficient pumps. This encouraged the participants to think

that their proposals could well lead to practical results.

.

.  .

.

The village is next to a large tank (reservoir) that catches

rainwater, but empties in the dry season

.

.  .

.

Below the tank, fields are irrigated from wells and boreholes; there

are sacred symbols at the spillway and next to wells

.

.  .

.

The groundwater project group visits wells and boreholes with a

hydrologist

.

.  .

.

The wells are deep and hundreds of years old

.

.

Sacred symbols by the well; learning water divining

.

.  .

.

When the electricity is on, farmers irrigate their fields

.

.  .

.

This is also the time to do the laundry; a plant indicator of water

.

.  .

.

Channels bring the water alongside the fields

.

.  .

.

The farmers open and close breaks in the channels to bring the water

to their crops

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

Before there were pumps, water was raised in bullock skins pulled up

by animals, and directed to the fields in stone-lined channels

.

.

Cloth drying in the sun; sacred objects by a well

Washing clothing

Laundry drying

.

.  .

.

Farmers dig up topsoil in the stream beds; shepherds store their hay

on rocky outcrops, and use thorn bushes for fences

.

.  .

.

A farmer with a betel nut plantation serves us drinking coconuts

.

.  .

.

Betel nut palms; one of three failed bore wells; the groundwater

group at the village gate (I am second from left)

.

.  .

.

The ancient columns in Sheshagiri's house were painted in traditional

colours while we were there

.

.  .

.

The microcredit group; groups at work

.

.  .

.

Intense discussions; Sheshagiri's sister and other resource persons

helped the groups

.

.  .

.

Courtyard in front of Sheshagiri's house; participants at work

.

.  .

.

Groups at work; the migration group filled a whole wall with notes

.

.  .

.

Discussions; Bindu, a neighbour and resource person with Sheshagiri;

loading the bus for the return trip

Timapamabeta Hill

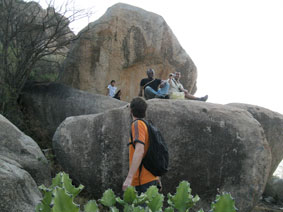

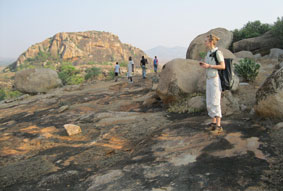

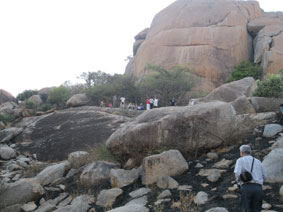

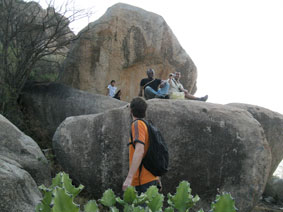

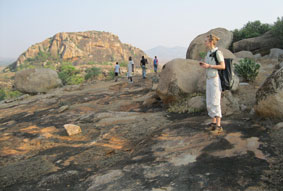

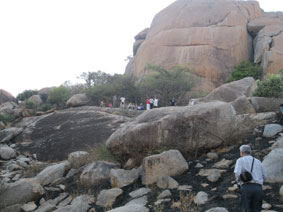

Early one morning we hiked up one of the granite hills near CK Pura to get a

better view of the countryside. We could not go to the top as there are

bears living there, and we saw recent droppings.

Views from the hill

A low-lying reservoir

.

.  .

.

At the start of the hike; the hill we climbed; on the way up

.

.  .

.

A pause to enjoy the view

.

.  .

.

The hill is mostly bare granite with large boulders; shepherds burn

off the vegetation to encourage grass

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

The view in the morning sun was beautiful

.

.  .

.

Rice cultivation with the water from the reservoir; the group of

hikers; a tractor trailer provided transport from and to the village

One night, some drummers from the

village came, and the dancing attracted quite a crowd, including even more

drummers

.

.  .

.

The village drummers; participants dancing

.

.  .

.

A large crowd gathered outside the house to watch

.

.  .

.

There were many styles of dancing

.

.  .

.

There was even a local demonstration of a scarf dance

.

.  .

.

The music went on for a long time

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

Everyone had a good time

After the dancing, the ladies of the house brought out some elegant saris,

and the female participants became Indian beauties.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

but that did not stop them from working

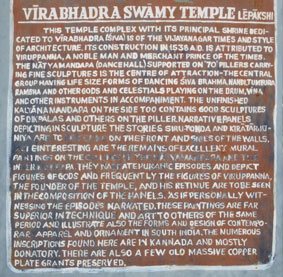

Lepakshi Temple

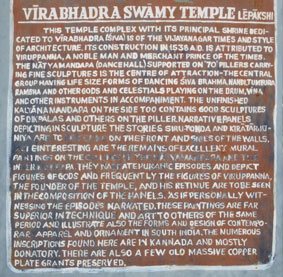

On the way back from CK Pura, we stopped at the Virabhadra Swamy Temple in

Lepakshi, constructed in 1538, but never finished. The previous MaDePro

class had also visited the temple in 2012.

.

.  .

.

Temple entrance

View towards Lepakshi from temple entrance

.

.  .

.

The guide explains the outer colonnade where pilgrims used to stay

during their visits

.

.  .

.

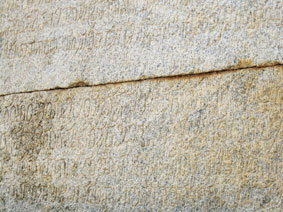

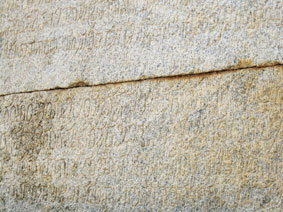

The temple walls are engraved with the full story of the temple gods

.

.  .

.

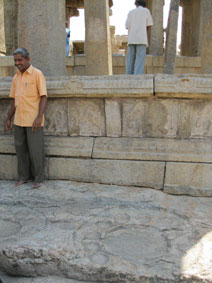

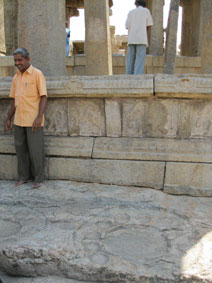

Footprints and an image of the founder of the temple are engraved in

the rock

.

.  .

.

The temple had many concentric circles covering all of Lepakshi, only

a few of which remain

.

.  .

.

The unfinished part of the temple with gods and godesses on all the

pillars

.

.  .

.

Shiva as an elephant, and its rat transporter; carvings in the temple

.

.  .

.

Snakes protecting a sacred stone

.

.  .

.  .

.

Wall marked by the plucked-out eyes of the temple architect;

participants admiring the sculptures

.

.  .

.

Temple left unfinished when work stopped after the architect was

unjustly punished

.

.  .

.  .

.

Places to worship; a giant footprint of a god

Lower part of the temple

.

.  .

.  .

.

Plates in the stone where the carvers ate; different parts of the

temple

.

.  .

.

Entrance to the dance hall before the inner temple; a suspended

column in the dance hall does not touch the ground

.

.  .

.

Entrance to the dance hall; dome over the centre; entrance to the

inner temple from the dance hall

.

.  .

.  .

.

Sculptures of dancers and musicians in the dance hall

.

.  .

.

Paintings on the ceiling of the dance hall

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

Paintings on the dance hall ceiling; giant bull at the entrance to

Lepakshi, originally part of the largest temple circle

Return to Bangalore

After our return to Bangalore, the development project groups each presented

their project before a jury of outside experts: the impacts of rural-urban

migration on the village; evaluation of microcredit schemes; introduction of

information technology into the schools; and problems of groundwater

management.

.

.  .

.

MaDePro coordinator Yuri Changkakoti; the jury of outside experts;

the audience of participants

.

.  .

.

Migration project group

.

.

Microcredit project group

.

.

Education project group

.

.

Groundwater project group

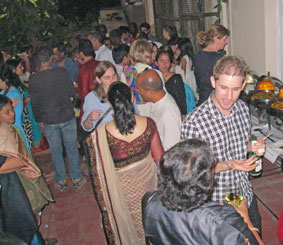

The course ended with a dinner reception at Swissnex

.

.  .

.

Reception in the garden at Swissnex

.

.  .

.

A thank you presentation from the participants to the Rao family for

hosting us so well

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

,

,

.

.  .

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.  .

.

.

.  .

.